News

Special offer – September 2016 DENTAL OFFER

by admin on September 1st, 2016

Category: Special Offers, Tags:

Pet of the Month – September 2016 – Daisy

by admin on September 1st, 2016

Category: Pet of the Month, Tags:

When young Daisy returned from her travels with a wounded and unstable right hock joint her owner brought her to the surgery straight away. Radiographs revealed the hock joint to be extremely unstable which necessitated a referral to an orthopaedic specialist.

Daisy’s hock was stabilised with an external fixator and bandaged. External fixation consists of inserting two or more pins each in undamaged areas of the bones proximal and distal to the fracture site. The pins are connected by clamps or putty to keep them rigid.

Undaunted by her escapade Daisy managed to escape from an open window on her first night home from the specialist. After a half hour chase she was caught and returned to what had been thought to be a secure enclosure, now with even tighter security. Her hock had to be re-radiographed the next day to check that no damage had been incurred and we are pleased to report that she is making very good progress.

Hyperthyroidism in Cats

by admin on September 1st, 2016

Category: News, Tags:

What is hyperthyroidism?

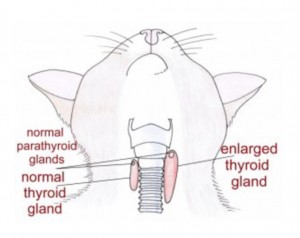

Hyperthyroidism is a relatively common disease of the ageing cat. It is typically the result of a benign (non-cancerous) increase in the number of cells in one or both of the thyroid glands. The thyroid glands are located in the neck although there is occasionally additional tissue within the chest. In the image the red shapes indicate approximately where the thyroid glands are located in a cat. The result of enlargement of the thyroid glands is an increased production of thyroid hormone within the body. Thyroid hormone controls the rate at which cells in the body work; if there is too much hormone, the cells work too fast. Despite many years of research the exact cause of hyperthyroidism remains unknown.

Cats fed almost entirely canned food have been reported to have an increased risk of developing hyperthyroidism but it is likely that there are many causes.

What signs do cats with hyperthyroidism get?

Hyperthyroidism is a disease of middle aged to older cats with an average age of onset of 12-13 years. Increased drinking and increased urination, weight loss, increased activity, vomiting, diarrhoea and increased appetite are often reported. Physical examination often reveals a small lump in the neck which represents an enlarged thyroid gland.

How is hyperthyroidism diagnosed?

A diagnosis of hyperthyroidism is made by the demonstration of increased levels of thyroid hormone in the blood stream. Thyroxine (T4) measurement is the initial diagnostic test of choice.

How is hyperthyroidism in cats managed?

- Medical treatment with either carbimazole or methimazole. These tablet medications are given once or twice daily lifelong. Side effects are uncommon but can occur. They include vomiting and reduced appetite. Very occasionally severe bone marrow or liver problems can be seen.

- Dietary treatment. A specific prescription diet can be fed to hyperthyroid cats to control the disease. The diet is very low in iodine. Iodine is an essential component of thyroid hormone and less dietary iodine means less thyroid hormone is produced. The diet must be fed exclusively (i.e. the cat must eat no other food). Dietary treatment does not lower the thyroid hormone levels as much as the other treatment options

- Surgical treatment. One or preferably both thyroid glands are removed with an operation. A short period of treatment with tablets is recommended prior to surgery. Anaesthesia can be a risk in older cats with hyperthyroidism that possibly have other concurrent diseases. There is a risk of a low blood calcium level after surgery if the parathyroid glands are removed with the thyroid glands. This can be a very serious problem if it is not recognised. Signs of a low blood calcium level can include facial rubbing, fits, tiredness, reduced appetite and wobbliness. Low blood calcium levels are relatively easily managed with oral medication and treatment is rarely necessary lifelong.

- Radioactive iodine treatment. Radioactive iodine is concentrated in the thyroid gland and destroys excessive thyroid tissue. The drug is given by injection under the skin. After the injection, cats need to spend 2-4 weeks in an isolation facility whilst they eliminate the radioactive material. Owners are not able to visit their pets whilst they are in isolation.

- Hyperthyroidism can mask underlying kidney problems and these can become apparent after treatment. Blood tests will be necessary to assess kidney function as well as the thyroxine level during/after treatment.

Can dogs get hyperthyroidism?

Dogs are rarely affected by hyperthyroidism and when it occurs in this species it is normally the result of a diet problem or cancer of the thyroid gland. Treatment for dogs with cancer of the thyroid gland can involve one or a combination of surgery, radioactive iodine, radiation therapy and chemotherapy. Unfortunately many dogs have advanced disease by the time the cancer is identified. The majority of dogs with thyroid cancer are not hyperthyroid; they typically retain normal thyroid function or become hypothyroid.

Pet of the Month – August 2016 – Brambie

by admin on August 1st, 2016

Category: Pet of the Month, Tags:

Brambie first visited the practice as a second opinion for recurrent bladder/urination problems. A scan revealed she had bladder stones which had not been picked up by her previous vet.

We surgically removed her bladder stones and are delighted to report that she is doing very well.

For your interest we include further information on bladder stones below.

What are the symptoms of struvite bladder stones?

The symptoms of bladder stones are very similar to the symptoms of an uncomplicated bladder infection or cystitis. The most common signs that a dog has bladder stones are hematuria (blood in the urine) and dysuria (straining to urinate). Hematuria occurs because the stones rub against the bladder wall, irritating and damaging the tissue and causing bleeding. Dysuria may result from inflammation and swelling of the bladder walls or the urethra, from muscle spasms, or due to a physical obstruction to urine flow caused by the presence of the stones. Veterinarians assume that the condition is painful, because people with bladder stones experience pain, and because many clients remark about how much better and more active their dog becomes following surgical removal of bladder stones.

Large stones may act almost like a valve or stopcock, causing an intermittent or partial obstruction at the neck of the bladder, the point where the bladder attaches to the urethra. Small stones may flow with the urine into the urethra where they can become lodged and cause an obstruction. If an obstruction occurs, the bladder cannot be emptied fully; if the obstruction is complete, the dog will be unable to urinate at all. If the obstruction is not relieved, the bladder may rupture. A complete obstruction is potentially life threatening and requires immediate emergency treatment.

My dog has struvite bladder stones. What does that mean?

Dogs, like people, can develop a variety of bladder and kidney stones. Bladder stones (uroliths or cystic calculi), are rock-like formations of minerals that form in the urinary bladder, and are more common than kidney stones in dogs. One of the more common urolith in the dog is composed of magnesium ammonium phosphate hexahydrate. The more common name for this type of bladder stone is “struvite bladder stone”.

How did my dog get them?

Normal dog urine is slightly acidic and contains waste products from metabolism including dissolved mineral salts and other compounds. Struvite is a normal component of dog’s urine and will remain dissolved as long as the urine is acidic and is not too concentrated. If the urine becomes exceptionally concentrated or if it becomes alkaline, struvite crystals will precipitate or fall out of solution.

In dogs, struvite bladder stones usually form as a complication of a bladder infection caused by bacteria that produce an enzyme known as urease. This enzyme breaks down the urea that is normally present in the urine causing an excess production of ammonia; this ammonia production then causes the urine to become alkaline. Ammonia in the urine also causes bladder inflammation. Under these environmental conditions, struvite crystals will precipitate out of solution and collect around any cells or debris that may have formed in the bladder as a result of inflammation. Female dogs tend to get these types of bladder infections and stones much more frequently than males, probably because their shorter, wider urethra makes it easier for bacteria to pass up the urethra into the bladder. In some studies, up to 85% of dogs with struvite bladder stones were female.

Other causes of alkaline urine such as certain kidney diseases, long-term use of diuretic drugs or antacids, and other conditions that cause elevated urine pH or elevated levels of urinary phosphorus or ammonia can also predispose a dog to the formation of struvite bladder stones.

How common are struvite bladder stones?

Bladder stones are somewhat common in dogs, and struvite stones are the most common; in clinical studies, up to 26% of all bladder stones were found to contain struvite. Together, struvite and calcium oxalate uroliths have been found to comprise over 85% of all uroliths submitted for laboratory analysis in a recent study. Based on the results of tens of thousands of stone analyses, it has been found that the number of struvite bladder stones has been declining in dogs while the number of calcium oxalate stones has been increasing during the past ten years. Struvite uroliths were noted to be more common in female dogs and calcium oxalate uroliths in male dogs. Breeds most commonly diagnosed with struvite and calcium oxalate bladder stones included: shih tzu, miniature schnauzer, bichon frisé, lhasa apso, and Yorkshire terrier.

How are struvite bladder stones diagnosed?

In some cases, your veterinarian may be able to palpate (feel) struvite stones in the bladder if the dog is relaxed and the bladder isn’t too painful. However, some stones are too small to be felt this way. Often, bladder stones are diagnosed by means of an x-ray of the bladder, or by means of an ultrasound. Struvite stones are almost always ‘radiodense’, meaning that they can be seen on a plain radiograph. However, sometimes bones or other overlying body parts will interfere with the ability to see bladder stones with regular x-rays, in which case your veterinarian may recommend a contrast study, a specialized technique that uses dye to outline the stones in the bladder, or a bladder ultrasound.

These imaging procedures will identify the presence of a bladder stone, but will not definitively tell your veterinarian the composition of the stone. The only way to be sure that a bladder stone is made of struvite is to have the stone analyzed at a veterinary laboratory.

In some cases, your veterinarian may make an educated guess about the type of stone that is present, based on the radiographic appearance and results of a urinalysis. For example, if x-rays show that there are one or more stones present in the bladder, and the results of the urinalysis show the presence of alkaline urine along with numerous struvite crystals, your veterinarian may make a presumptive diagnosis of struvite bladder stones and recommend treatment accordingly.

How are struvite bladder stones treated?

There are three primary treatment strategies for struvite bladder stones:

1) Feeding a special diet to dissolve the stone(s)

2) Non-surgical removal by urohydropropulsion

3) Surgical removal

1) Feeding a special diet: The use of special therapeutic diets to dissolve struvite bladder stones is often recommended in cases where the risk of a urinary tract obstruction is relatively low. These diets typically are restricted in protein, phosphorus and magnesium and are formulated to promote formation of acidic urine (with a pH less than 6.5). This formulation helps dissolve struvite stones that are already present in the urine, and prevents formation of further stones. Dissolution of the stones is further enhanced by increased water intake, which will serve to dilute the urine.

Since most dogs with struvite bladder stones developed them as a result of a bladder infection, the dog will also be placed on antibiotic therapy while the stones are being dissolved. This is important because, as the layers of stone are dissolved, bacteria that have become trapped in the layers of stone are released into the bladder; if left untreated these bacteria can set up another infection. Some dogs may experience dissolution of struvite stones within two weeks while others may take up to 12 weeks. Your dog will need to have antibiotics during this entire period of time. If your dog is placed on dietary therapy to dissolve the bladder stones, your veterinarian will recommend that a urinalysis and bladder x-rays should be performed approximately every four to six weeks during treatment.

Some bladder stones can be ‘mixed’ or composed of multiple layers of different types of mineral, which may complicate treatment. If follow-up x-rays show that the stones are no longer dissolving, this may indicate that the stones are mixed, and the treatment plan may need to be adjusted.

2) Non-surgical removal: If the bladder stones are very small it may be possible to pass a special catheter into the bladder and then flush the stones out, in a technique called urohydropropulsion. In some cases, this procedure may be performed with the dog under heavy sedation, although general anesthesia is often necessary. If your veterinarian has a cystoscope, small stones in the bladder or urethra can sometimes be removed with this instrument, thus avoiding the need to cut the abdomen and bladder open. Either of these procedures may also be used to obtain a sample stone for analysis so that your veterinarian can determine if dietary dissolution is feasible.

3) Surgical removal: Surgery is indicated in dogs that have a large number of stones in their bladder, if there is an increased risk that the patient will develop an obstruction in the urinary tract, or if the client wishes to have the problem resolved as quickly as possible. Male dogs are at a much higher risk of developing an obstruction in the urinary tract as a result of bladder stones, so when bladder stones are diagnosed in a male dog, your veterinarian will often strongly recommend surgical removal. Surgery is also indicated if dietary treatment was not successful in eliminating the stones, or If it appears that the stones are composed of a mixture of mineral types. Your veterinarian will discuss the appropriate treatment strategy for your dog, based on your individual situation.

Are there any other treatment options?

In some selected referral centers, another option may be available to treat bladder stones. This option is ultrasonic dissolution, a technique in which high frequency ultrasound waves are used to disrupt or break the stones into tiny particles that can then be flushed out of the bladder. It has the advantage of immediate removal of the offending stones without the need for surgery. Your veterinarian will discuss this treatment option with you if it is available in your area.

How can I prevent my dog from developing struvite bladder stones in the future?

Dogs that have experienced struvite bladder stones will often be fed a therapeutic diet for life. Diets lower in protein, phosphorus and magnesium and promote acidic urine are recommended. The preventative diet is NOT the same as the diet that promotes dissolution of the stones. In certain cases, medications to acidify the urine may be required. In addition, careful routine monitoring of the urine to detect any signs of bacterial infection is also recommended. Bladder x-rays and urinalysis will be performed one month after successful treatment, dietary or surgical, and then every three to six months for life. Dogs displaying any clinical signs of urinary tract infections such as frequent urination, urinating in unusual places, painful urination or the presence of blood in the urine should be evaluated immediately. Keep in mind that the greatest risk factor for developing struvite bladder stones in the dog is a urinary tract infection.

Chronic Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD) in Dogs

by admin on August 1st, 2016

Category: News, Tags:

Chronic inflammatory enteropathy (or CIE) is a disease that causes inflammation of the bowel. It has some similarities to a human disease called Crohn’s disease. The inflammation can affect any or all of the stomach, small bowel and large bowel (colon).

What are the signs of chronic inflammatory bowel problems in dogs?

Gastrointestinal (bowel) signs are considered chronic when they have been present for three weeks or more and often clinical signs will come and go. The most common signs associated with gastrointestinal tract disease in dogs include vomiting and diarrhoea. It is important to remember that diarrhoea is a term used to describe altered stool frequency as well as altered stool consistency. Blood and mucus are sometimes seen mixed with the stool. Abdominal pain, ‘squeaky’ guts (this is called ‘borborygmi’) and wind can also be seen. Some cats with chronic inflammatory bowel disease will have no vomiting or diarrhoea and their main sign will be reduced appetite.

What causes chronic inflammatory enteropathy in dogs?

The gastrointestinal signs seen in chronic inflammatory enteropathy arise due to inflammation of the wall of the intestines and/or stomach. The initial cause of the inflammation is often unknown; environmental and genetic factors are thought to play a role along with an abnormal response of the body’s immune system that normally fights infection. Chronic inflammatory enteropathy is generally considered to be an ‘idiopathic’ disease (i.e. a disease with no known underlying cause). The diagnosis is one of exclusion and the diagnosis can only be made if other possible causes of the signs have been excluded.

Chronic inflammatory enteropathy is not a single disease process but it is actually a catch-all term applied to a number of diseases with similar signs. It encompasses food responsive disease (FRD), antibiotic responsive diarrhoea (ARD) and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).

- Food responsive disease is diagnosed when a dog or cat has clinical signs of gastrointestinal tract disease that responds to dietary modification.

- Antibiotic responsive diarrhoea is the term used when gastrointestinal tract signs respond to antibiotic(s) and relapse when antibiotics are stopped. The immune system is thought to have an exaggerated response to ‘normal’ gut bacteria in patients with this disease. It is important to note that antibiotics are not normally indicated in sudden (acute) onset diarrhoea.

- Inflammatory bowel disease has a complex set of underlying causes. It is diagnosed with bowel biopsies that are normally taken with the aid of a camera (endoscope) meaning that surgery is not necessary. It is normally managed with steroid therapy.

Which breeds can be affected by chronic inflammatory enteropathy?

Chronic inflammatory enteropathy can occur in any breed of dog, but certain breeds such as German Shepherds, Soft-coated Wheaten terrier and Irish Setters are known to have an increased risk. It is typically a disease of the middle aged dog but any aged dog can be affected. Cats can also get CIE.

How is chronic inflammatory enteropathy diagnosed?

Chronic inflammatory enteropathy in dogs is normally diagnosed on the basis of history, blood tests, abdominal imaging (typically an ultrasound scan) and sometimes camera evaluation of the upper and/or lower bowel.

How are chronic inflammatory bowel problems in dogs treated?

Dependent upon the severity of the presenting signs, a change in diet may be the first treatment undertaken by your vet. Generally diet trials are performed using a diet that contains a single protein source or one where the proteins are broken down to such a small size (hydrolysed) that they are not recognised as ‘foreign’ by the immune system in the bowel. Some vets prefer to use a single protein source that the patient is unlikely to have been exposed to before (i.e. duck or venison). The diet is normally fed for a minimum of two to four weeks but many dogs respond sooner. If the signs respond to dietary therapy, a diagnosis of food responsive disease is made and dietary therapy is continued long term.

If patients fail to respond to a diet trial or only partially respond, antibiotics may be trialled. If the signs respond, a diagnosis of antibiotic responsive diarrhoea is made.

If the animal’s clinical signs persist despite dietary change or antibiotic therapy, or if the clinical signs are particularly severe, camera examination of the bowel will be performed. This is called endoscopy and the procedure is always done under general anaesthesia in animals. Small biopsies are taken from the bowel during this procedure. Assuming inflammation is identified on the biopsies, a diagnosis of inflammatory bowel disease is made. Inflammatory bowel disease is managed with drugs that suppress the immune system’s exuberant response. A steroid called prednisolone is often the first choice medication in both dogs and cats. Additional medications such as ciclosporin and chlormabucil are sometimes used.

What is the outlook for chronic inflammatory bowel disease in dogs?

The outlook for patients with chronic inflammatory enteropathy is dependent upon the severity of the signs and the response to treatment. Many patients will experience intermittent flare ups of their disease long term despite therapy but these are typically milder and shorter in duration once animals are receiving appropriate treatment. Unfortunately a very small proportion of dogs with IBD have disease that is not responsive to drug therapy.

Pet of the Month – July 2016 – Hedgie!

by admin on July 1st, 2016

Category: Pet of the Month, Tags: Tags: hedgehog, pet

This week’s Pet of the Month is a small hedgehog we have chosen to highlight the fantastic work our vets and nurses do treating wildlife. A few years ago we were very fortunate to have a Wildlife Unit built in our garden funded by The Body Shop and WADARS Animal Rescue. This small hedgehog was brought in to us injured, by a member of the public. We checked him over thoroughly under anaesthetic and cleaned up his wounded leg. He is now starting to eat and recover. We hope he will be moving on to a hedgehog rehabilitation centre shortly and in due course ‘Hedgie’ should be able to return to the countryside.

Episodic Weakness and Collapse

by admin on July 1st, 2016

Category: News, Tags: Tags: collapse, dog, weakness

What is Episodic weakness and collapse?

Essentially, ‘episodic weakness and collapse’ refers to involuntary falling over! Dogs are more commonly presented to veterinary surgeons with this problem than cats. Syncope (pronounced sin-coh-pea) is the technical term for fainting when the patient temporarily loses consciousness. Collapse, such as fainting, may be completely benign and require no treatment. However, in some circumstances it is due to a life-threatening situation that requires a specific treatment.

Remember these conditions are both Involuntary (the patient has no control over them) and intermittent or ‘episodic’ and the patient may be completely normal between bouts. There are no seizures or fits as we see in Epilepsy. Also, before starting our investigations, we need to be as sure as possible that involuntary collapse is truly occurring. If a dog is choosing to lie down, for instance because of tiredness or heat exhaustion, or because of feeling faint after pulling hard on the lead this is not collapse.

What causes episodes of weakness, collapse or fainting?

The causes are many and varied and can involve:

- The airways

- The heart and blood vessels

- The nervous system – brain, spinal cord, peripheral nerves

- The muscles, bones and joints

- A malfunction of one or more chemical processes occurring in one of a number of body organs (these are usually referred to as ‘Metabolic’ causes).

To further complicate matters there are plenty of potential causes of collapse within each of these broad categories. So, what might seem to be a relatively ‘simple’ clinical presentation can turn into the proverbial search for a needle in a haystack when it comes to finding out the cause of the problem.

Investigations can therefore be costly, frustrating and extremely time consuming for all concerned. For example, it is quite common for blood samples to be sent to more than one specialist laboratory and some of these may be outside the UK. Finally getting all the results together can take several days or even weeks. It can be a trial of patience waiting for such tests but it is better to wait for accurate results than to choose a more rapid but less helpful alternative.

How can pet owners and carers help in getting to a diagnosis?

Getting to a diagnosis is clearly very important so we know how to treat effectively. You can help your vet a lot in this regard! It is often very helpful if video footage of the events occurring can be provided as sometimes this may show important information which to the untrained eye may not be obvious. Your vet may well not see the event you are concerned about as by their very nature these are intermittent events.

It is very helpful to know the following:

- What a pet is doing just before he or she collapses

- What he or she does during the collapse

- What he or she does after the collapse

Your vet will then want to perform a thorough clinical examination. Ideally, the information you provide and the results of your vet’s examination will give diagnostic ‘clues’ as to which direction in which to look first. If these findings make one particular cause of collapse more likely than others then this gives a far better chance of determining the cause. A problem arises where signs are vague and do not allow us to ‘home in’ on a particular group of possibilities. In these circumstances unfortunately investigation needs to be very broad-based and we would start by evaluating for the most common causes of collapse.

How is collapse investigated?

There is no single test that will evaluate the patient for all causes of collapse. Tests are picked on an individual basis according to how valuable the clinician expects the test to be in a particular case. This is why the intial information and history is so important because it will help the clinician to be more specific with the tests performed and therefore more likely to discover the cause.

Each case is different but investigations will often involve

1. Blood tests to look for metabolic causes

2. Assessment of the heart by an electrocardiogram (ECG), an echocardiogram (heart ultrasound) and chest x-rays. In some patients where an intermittent electrical abnormality is suspected, the patient will be fitted with a device to perform an ECG for 24 hours in an effort to ‘catch’ the irregular heart rhythm. This special ECG device is called a Holter monitor and it is connected to sticky pads which adhere gently to the skin to allow the rhythm of the heart to be recorded for extended periods of time and even at home.

If these tests are normal then further testing depending on the remaining clinical possibilities is indicated. Sometimes further tests may be advised straight away or in some instances it may be worth performing these after a delay both to make sure that the problem is persisting and also to allow some time for further ‘clues’ pointing to a particular diagnosis to develop.

Is a specific diagnosis always found?

In some instances, despite lengthy and thorough investigation, no cause of the collapse is found. The same is also true in human medicine. Sometimes this may be because the cause is either benign or occurring so rarely that the cause is not caught ‘in the act’. Other causes of collapse may remain undiagnosed because some potential causes are simply not possible to evaluate in dogs and cats, particularly tests that in humans would require a period of voluntary bed rest – clearly this is not possible to achieve in a dog or cat.

How is Episodic weakness and collapse treated?

This completely depends on identifying the cause. Appropriate treatment is then instigated.