News

Special Offer – January 2017 – Dental Offer

by admin on January 3rd, 2017

Category: Special Offers, Tags:

Special Offer – December 2016 – Arthritis Awareness Month

by admin on December 1st, 2016

Category: Special Offers, Tags:

Pet of the Month – December 2016 – Smudgey

by admin on December 1st, 2016

Category: Pet of the Month, Tags:

Smudgey is giving us a reproving look from the depths of a buster collar that should prevent him removing his indwelling urinary catheter.

The catheter had to be placed under anaesthesia in an emergency procedure to relieve a potentially life-threatening condition called urethral obstruction.

The catheter had to be placed under anaesthesia in an emergency procedure to relieve a potentially life-threatening condition called urethral obstruction.

Urethral obstruction is a problem that occurs almost exclusively in male cats. This is because the urethra of a male cat is much longer and much narrower than that of a female cat, and so is more susceptible to becoming blocked.

Urethral blockage is not a common condition, but when it occurs it is painful, the cat will be unable to urinate despite repeated efforts, and it is a life-threatening emergency as it can cause acute kidney failure and death within 2-3 days if not managed appropriately

What are the signs of urethral obstruction?

A cat with urethral obstruction will usually show:

- Repeated attempts to urinate that are unproductive

- Crying or discomfort when straining to urinate

- Increased agitation, and there may be some vomiting

Depending on the underlying cause, you may also have noticed some other changes in your cat’s urinating behaviour over the preceding few days such as increased frequency of urination, straining, discomfort or even some blood in the urine.

Contact your vet immediately if you think your cat may have an obstructed urethra, as this is an emergency situation.

What causes urethral obstruction?

Several underlying conditions can cause obstruction of the narrow urethra of a male cat, including:

- A ‘plug’ in the urethra – this is usually an accumulation of proteins, cells, crystals and debris in the bladder that accumulates and lodges in the urethra

- A small stone (urolith) or an accumulation of very small stones – these form in the bladder but may become lodged in the urethra

- Swelling and spasm of the urethra – during inflammation of the bladder and urethra, whatever the cause, the inflammation may cause swelling of the wall of the urethra which may contribute to blockage, and in a number of cases the inflammation and irritation causes the muscle around the urethra (the urethral sphincter muscle) to go into spasm – this too can cause obstruction if the cat is not able to relax the muscle.

How is urethral blockage managed?

If your cat’s urethra is blocked, the vet will need to relieve the obstruction quickly.

Blood tests may be important to see if there are any significant complications. In particular, cats with a blocked urethra may develop acute kidney failure and may develop very high blood potassium concentrations; these are life-threatening complications that should be checked when possible.

X-rays or ultrasound may be needed to help determine the underlying cause of the obstruction and to help determine the best treatment method.

Under anaesthesia a catheter is passed into the urethra (via the penis) so that fluids can be infused to help flush out the obstruction (or sometimes to push it back into the bladder). These procedures have to be done very carefully to avoid damaging the delicate lining of the urethra.

If the obstruction is caused by spasm of the urethral muscle, simply sedating or anaesthetising the cat may be sufficient to allow easy passage of a catheter into the bladder.

What happens after the obstruction is relieved?

Once the obstruction has been relieved, the vet will want to infuse a sterile saline solution into the bladder via the catheter so that all the blood and debris (that will inevitably be present in the bladder) can be washed out. This is usually repeated several times to remove as much debris as possible to reduce the chance of re-obstruction.

Once this has been done, the vet will decide whether the urinary catheter can be removed. If there has been a severe blockage, your vet may want to leave a catheter in for a few days (usually no more than 2-3 days) to ensure urine can be produced while treatment is commenced for the underlying disease and inflammation.

What other treatments are given?

Further treatment depends on the underlying cause of the obstruction, the severity of the obstruction, and what (if any) complications have arisen. Any damage to the kidneys may be completely reversible, but cats will often have to receive intravenous fluids for several days if the kidneys have been affected. In addition to intravenous fluids, other drugs commonly used to help manage cats include:

- Other pain-killing (analgesic) drugs

- Drugs to help relieve spasm of the urethra (spasmolytics)

- Anti-inflammatory drugs to relieve the swelling in the urethra

Long-term management of the cat with urethral obstruction

In the short-term, while the initial swelling in the urethra settles down, cats may need to be on anti-inflammatory drugs, spasmolytics, and perhaps analgesics for several days and even up to a week or two.

Longer term, management is aimed at the underlying cause of the urethral obstruction. Cases associated with uroliths (stones in the urethra and bladder) will need to be managed with special diets to reduce the risk of their recurrence. Most cats with urethral spasm or urethral plugs are thought to have underlying feline idiopathic cystitis. These cats should be managed with painkillers and the aim of reducing stress.

If repeated episodes of obstruction occur despite appropriate management, in some cases a surgical operation can be performed (called perineal urethrostomy) to help open and widen the narrow end to the urethra. This should not be regarded as a first-line therapy though as it does not deal with the underlying cause, and the surgery can sometimes be associated with complications such as the risk of stricture formation and an increased risk of bacterial urinary tract infections.

POISONS PUT LITTLEHAMPTON PETS IN PERIL

by admin on December 1st, 2016

Category: News, Tags:

Poisons put Littlehampton pets in peril, as 95% of vets report cases.

Fitzalan House Vets warn local pet owners to guard against poisonous perils after the British Veterinary Association’s (BVA) Voice of the Veterinary Profession survey showed 95%of South-East region companion animal vets had seen cases of toxic ingestion or other toxic incidents over the last year.

Across the UK, vets saw on average one cases of poisoning every month, with chocolate (89%), rat poison (78%) and grapes (60%) the most common poisons that vets had treated. Other poisons involved in the cases vets had seen included:

Other less common cases involved xylitol poisoning from chewing gum, poisoning from wild mushrooms and fungi, as well as horse worming products ingested by dogs.

Vets know that sometimes owners can take every precaution and accidents still happen. If an owner suspects their pet may have ingested or come into contact with any harmful substance they should contact us immediately on 01903-713806 for advice.

BVA President Gudrun Ravetz said:

“These findings from BVA’s Voice of the Veterinary Profession survey show how common incidents of pet poisoning are and underline that owners must be vigilant especially with prying pets. The top five poisoning cases seen by vets include foods that are not toxic to humans but which pose a significant risk to pets such as dogs, like chocolate and grapes, alongside other toxic substances such as rat poison and antifreeze. Owners can take steps to avoid both perils – keep human food away from and out of reach of pets and make sure other toxic substances and medicines are kept securely locked away in pet-proof containers and cupboards.”

Special Offer – November 2016 – Diabetes Awareness Month

by admin on November 3rd, 2016

Category: Special Offers, Tags:

Pet of the Month – November 2016 – Bruce

by admin on November 3rd, 2016

Category: Pet of the Month, Tags:

Poor Bruce! This is not the first time our practice cat has featured in this newsletter. At present Bruce is suffering from pancreatitis and is in our hospital.

Pancreatitis in cats has two forms, acute and chronic, which are usually diagnosed by symptoms and by ruling out other diseases. There are diagnostic tests for pancreatitis, but they are not always accurate, they can be costly, and can be quite invasive for a definitive diagnosis. Pancreatitis can also predispose your cat to other disease processes.

The pancreas is an organ that makes two primary products – digestive enzymes and insulin. Normally the digestive enzymes are released in an inactive form and are not activated until they reach the intestinal tract. This is to prevent the enzymes that are designed to break down food from coming into contact with the delicate pancreatic tissue.

In pancreatitis, for reasons yet unknown to us, these digestive enzymes will become activated while they are still in the pancreas. This results in significant inflammation and irritation to the pancreatic tissue, which can also cascade to other surrounding tissues such as the liver and intestinal tract. This can lead to secondary bacterial infections in the pancreas.

If the activation of the digestive enzymes is significant enough, then your cat can develop acute pancreatitis which can range from mild to severe and life threatening. If the activation of the digestive enzymes remains mild and continues long term, then your cat may develop chronic pancreatitis, which can result in the development of scar tissue in the pancreas, and eventually pancreatic insufficiency and predisposition to diabetes. It has been estimated that 30% or more of cats have chronic pancreatitis, but many may never show symptoms.

Acute pancreatitis:

Symptoms - Every cat will have different symptoms, some may have several, and some may have only one.

- Intense vomiting: Your cat may vomit multiple times over a period of hours or days, and may not be able to keep food down. This needs to be addressed quickly to prevent dehydration.

- Pain: Your cat may be sitting in a hunched position with their head tucked, or not want to be picked up or touched. Acute pancreatitis is very painful in all mammals.

- Anorexia:Your cat may be feeling intensely nauseous and painful, so it is unlikely that they will want to eat.

- Lethargy: Your cat may be extremely tired and lethargic.

- Diarrhoea: If your cat’s pancreas is so inflamed that it is not secreting digestive enzymes into the small intestine, then any food that your cat does eat may come out as diarrhoea with a very foul odour.

Diagnosis - With acute pancreatitis, we will need to begin treatment immediately. How we treat at this point will be based on the severity of the symptoms and blood sample results.

- Blood tests: As well as general haematology and biochemistry tests there are pancreas specific tests such as fPLI – this stands for feline pancreatic lipase immunoreactivity which can be elevated in pancreatitis in cats. However, while a positive test can confirm a diagnosis of pancreatitis, a negative test does NOT rule it out. It is possible to have a false positive with this test. The accuracy of this test has been estimated to be between 50-80%. So, while we may use this test to try and confirm a diagnosis of pancreatitis, we will not use it to make an initial diagnosis.

- Ultrasound: For an experienced ultrasonographer, this can be a good way to diagnose pancreatitis, by finding an enlarged, thickened pancreas on ultrasound. However, this requires a more advanced skill level of ultrasonagraphy than most general practitioners have.

- Biopsy: This is considered the gold standard for a 99.9% accurate diagnosis. However, this requires exploratory abdominal surgery which is invasive to your already sick cat, and it can take 2-3 days to get the histopathology results, so we do not do this routinely.

Treatment - The goal of treatment for acute pancreatitis is to reduce your cat’s pain and nausea, stabilize any electrolyte abnormalities, treat any secondary infections, and reduce the inflammation until your cat is able to heal.

- Pain management: This is one of the most important aspects of treating acute pancreatitis. Commonly used drugs are: Buprenorphine. This is a narcotic that has show to have excellent pain control in cats. This is our most common first line pain management for acute pancreatitis.

- Nausea: We have several anti-nausea medications that we will use in cats with acute pancreatitis. Most commonly used is Cerenia (maropitant). This is a fairly new drug that has quickly become our first line of defense for nausea in cats. This drug not only reduces nausea and vomiting, but it also has anti-inflammatory and anti-pain properties.

- Reducing gastric acid secretion in the stomach can help an already nauseated cat. We often use omeprazole.

- Antibiotics: We may use antibiotics to treat any secondary infections.

- Intravenous fluids: If your cat is having a hard time staying hydrated due to vomiting or not drinking, or if your cat has abnormal electrolytes, then we will start intravenous fluid therapy.

- Syringe feeding: If is very important that you cat eats. If they are too nauseous to eat, we may syringe feed them a very bland diet or a prescription diet.

Possible long term effects: Acute pancreatitis can lead to destruction of a fair amount of pancreatic tissue. How much tissue is affected can determine what happens next. Some of the more common sequelae are:

- Scar tissue: After the inflammation subsides, there is a chance of scar tissue developing in the healing process. As long as there is enough healthy tissue remaining, then your cat may never have any additional problems.

- Chronic pancreatitis: This is what happens when your cat’s pancreas continues to have low grade chronic inflammation. This can result in regular vomiting and anorexia episodes.

- Pancreatic insufficiency: When too much of your cat’s pancreas that makes digestive enzymes is destroyed, either by severe acute pancreatitis, or by chronic pancreatitis, eventually the pancreas will not be able to make enough enzymes to digest food. Your cat may then have large fluffy diarrhea and an increase in vomiting. This can be treated by giving your cat synthetic digestive enzymes.

- Type I diabetes: When enough of your cat’s pancreas that makes insulin is destroyed, it will not be able to make enough insulin to counteract the glucose in the body. Your cat may then develop diabetes and will need to be started on insulin injections.

Chronic pancreatitis:

The symptoms of chronic pancreatitis are very similar to acute pancreatitis, but on a milder scale. A common pattern we will hear is that your cat will vomit several times a day for a few days, not want to eat, and may act uncomfortable and lethargic, and then a few days later, will be fine until the next episode. These symptoms can also be similar to inflammatory bowel disease, so we may ask you lots of questions about exactly what goes on with each episode, and frequency to try and distinguish between the two.

Diagnosis again is similar to acute pancreatitis, but it can be harder as the blood work will be more likely to look normal, fPLI will only be positive if there is significant inflammation, and ultrasound will be even harder to detect. There is a blood test available that will test for two pancreatic enzymes and two intestinal enzymes to try and differentiate between pancreatitis and inflammatory bowel disease, but if it is negative, it still doesn’t rule either one out for sure.

Treatment most commonly is symptomatic, with pain medications, antibiotics, and anti-nausea medications. For cats who do have routine flare ups of chronic pancreatitis, we may want to treat long term with Cerenia as a preventative. We have a few other preventative treatment options as well if Cerenia is not an option.

While pancreatitis is one of the more painful and potentially nauseating diseases we can see in cats, as you have just read above there are things we can do to decrease its effects and help your cat to feel better.

Corneal Ulcers in Dogs and Cats

by admin on November 3rd, 2016

Category: News, Tags:

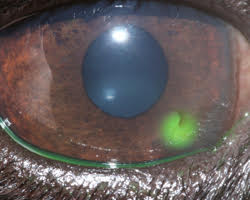

Corneal ulcers are defects of the ‘cornea’, the clear ‘window’ of the eye.

What is the cornea?

The cornea is a very special tissue that is completely transparent. In contrast to the skin, it lacks pigment and even blood vessels to maintain its transparency. The cornea is very rich with nerves, making it a very sensitive tissue. This is the reason why even small particles such as dust on the surface of the eye can be so uncomfortable.

The cornea is made of three layers:

- a very thin outer layer (epithelium)

- the thick middle layer (stroma)

- a very thin inner layer (endothelium)

All three layers are important for the cornea to work. The outer layer or ‘epithelium’ can be thought of as a layer of cling film that forms the surface of the cornea and protects it from infections. It works as a shield to the eye. The thick middle layer or ‘stroma’ is what gives the cornea its strength and stability.

What are corneal ulcers?

Corneal ulcers are classified by the depth, depending on the layers they affect.

If only the epithelium is missing this is classified as a ‘superficial ulcer’ or surface defect only. If the ulcer reaches into the stroma it is classified as a ‘deep ulcer’.

corneal ulcer

While superficial or surface ulcers are uncomfortable and present a risk of infection to the eye; the eye is not at risk of bursting unless additional problems occur. However when the ulcer gets deep the eye becomes weak and can even perforate. Deep ulcers lead to visible indentations on the surface of the eye and can be accompanied by inflammation inside the eye.

Signs of corneal ulcers usually include eye pain (squinting, tearing, depressed behaviour) and ocular discharge, which can be watery or purulent. Sometimes a lesion may already be visible on the surface of the eye. In this case it is particularly important to seek help from your veterinary surgeon as soon as possible.

How is a corneal ulcer diagnosed?

To diagnose a corneal ulcer your vet may use a special dye that highlights any defects of the surface layer by staining the underlying tissue green (see the image at the start of this article). This test is called the fluorescein test.

Why do corneal ulcers occur?

When the presence of an ulcer has been confirmed, it is important to try and find a reason for it. Most ulcers occur due to an initial trauma. This is more likely to happen in dogs and cats with very prominent eyes (also called ‘brachycephalic’ animals), for example in Pugs and Pekingese dogs or Persian cats. In cats the flare up of a Feline Herpes Virus infection is also a common cause for the development of a corneal ulcer. Many conditions can increase the risk of corneal ulcers. Reduced tear production is a common contributing factor, but other conditions such as an incomplete blink, in-rolling of the eyelid (also called ‘entropion’) or eye lid tumours may contribute to the occurrence, but even more so may interfere with the healing process.

How are corneal ulcers treated?

To treat an ulcer it is essential that the underlying cause is identified and if possible corrected. This will stop the ulcer from getting worse and allow the eye to heal as quickly as possible. The treatment plan will usually include eye drops to treat or prevent infection but may include other medication depending on the cause and severity of the ulcer. Painkillers and/or antibiotics by mouth may also be necessary.

Do any corneal ulcers require an operation?

If an ulcer is deep or the cornea is even ruptured, surgery is required to save the eye. Different techniques are available, but all of them place healthy tissue into the defect to stabilise the cornea. Very small suture material, as thin as a human hair, is used to repair the cornea and an operating microscope should be used to handle the small and very fine structures of the eye.

In most patients the healthy tissue is taken from the same eye from an area adjacent to the corneal ulcer.

The pink tissue next to the cornea (the conjunctiva) can be used for that to place a ‘conjunctival pedicle graft’ into the defect. More commonly, healthy corneal tissue attached to conjunctiva is used as it provides more strength to the wall of the eye. This is called a ‘corneoconjunctival transposition’ (Figure 5).

Corneal grafts are also possible but rely on the often limited availability of donor corneal tissue. Grafting surgeries are very successful in saving eyes, but can lead to scaring of the cornea leaving it less transparent in areas.

How can corneal ulcers be prevented?

Particularly in patients with prominent eyes, regular eye examinations should be performed to detect weaknesses in the corneal health. Indications of that may include white or brown marks on the surface of an otherwise comfortable eye or sticky discharge that continues to recur. Any painful eye should be presented to a veterinary surgeon as soon as possible.

Eyes may be cleaned with tap water that ideally should be boiled and cooled down again, using a lint-free towel. This should however not replace or delay the visit to a veterinary surgeon, as many ulcers require medication to achieve fast healing and prevent ill effects to the transparency of the cornea and therefore the sight of the dog or cat. Particularly; if a deep indentation or bulging tissue is noted on the surface, the eye should not be manipulated to prevent any additional damage.

Corneal ulcers are best prevented but if they are present they should be treated as soon as possible to stop them from getting bigger and deeper.

Special offer – October 2016 FIREWORKS

by admin on October 7th, 2016

Category: Special Offers, Tags:

Pet of the Month – October 2016 – Margot

by admin on October 7th, 2016

Category: Pet of the Month, Tags:

Margot is currently doing really well, recovering from an operation to correct “cherry eye’.

Cherry eye, or prolapse of the gland of the third eyelid, is quite common in small dogs and refers to a pink mass protruding from the animal’s eyelid;. The prolapsed gland itself rarely causes discomfort or damage to the eye, so the repair is mostly cosmetic. Most people choose to repair it, because it can have a very unpleasant appearance.

The gland contributes about 40% of the total tear-production of the eye and it is therefore imperative to aim to preserve the gland if possible as removal can cause a dry eye which can lead to damaged vision. If this does happen, it is controllable with medications, but it is preferable to prevent it. The most common surgical approach is a technique in which the gland is re-positioned using a mucosal pocket, creating a new envelope for the gland to sit within, but taking care to leave a few millimetres on either side to allow tears to drain freely. The unaffected side is often operated on pre-emptively.

Addisons Disease

by admin on October 7th, 2016

Category: News, Tags:

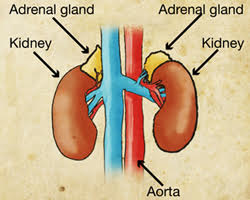

What is Addison’s disease?

Hypoadrenocorticism (or Addison’s disease as it is more commonly known) is a disease where the body does not produce enough steroid hormone. Steroids in the body are primarily produced by the two adrenal glands which are found in the abdomen close to the left and right kidneys. The main steroid hormones produced by the body are called aldosterone and glucocorticoid.

Aldosterone is important in the maintenance of normal salt and water balance in the body. Glucocorticoids have widespread effects on the management of proteins and sugars by the body.

Glucocorticoid release from the adrenal glands is under the control of a substance produced in a gland in the brain called the pituitary gland. Aldosterone release is regulated by a hormone system and by blood potassium levels.

What causes Addison’s disease?

Addison’s disease is normally caused by destruction of tissue of the adrenal gland.In the majority of cases the destruction does not have an identifiable underlying cause (this is called ‘idiopathic disease’).In most cases the adrenal glands stop producing both aldosterone and glucocorticoid (known as ‘primary hypoadrenocorticism’). Occasionally, only glucocorticoids are lacking (known as ‘atypical hypoadrenocorticism’).

Sometimes Addison’s disease occurs in combination with diseases of other glands such as hypothyroidism (this is a disease that causes thyroid hormone levels in the blood stream to be low).

Which animals are at greater risk of developing Addison’s disease?

Addison’s disease is a rare disease in the dog; however, it probably occurs more often than is recognised. It is a very rare disease in the cat. Any breed of dog can be affected with Addison’s disease but a predisposition has been shown in Nova Scotia Duck Tolling Retrievers, Bearded Collies, Portugese water dogs and Standard Poodles. In addition Great Danes, Rottweilers, West Highland White Terriers and Soft Coated Wheaten Terriers appear to be at greater risk. Addison’s disease appears to be a disease of the young and middle-aged dog. Approximately 70% of dogs with naturally occurring Addison’s disease are female.

What are the signs of Addison’s disease?

Presenting signs in Addison’s disease vary from mild to severe and do not typically focus attention on any one major body system. The presentation of sudden onset Addison’s disease (the so called ‘Addisonian crisis’) is collapse and profound dullness. Some patients have a slow heart rate. Addison’s disease is easily confused with many other diseases. The presenting signs in longer standing disease are vague and may include vomiting, reduced appetite, tiredness, weight loss, diarrhoea, increased thirst and increased urination.

How is Addison’s disease diagnosed?

Blood tests can sometimes reveal characteristic changes in salt levels. Kidney numbers can also be elevated and mild anaemia (low red blood cells) is not uncommon. The salt changes occur as a result of a deficiency of aldosterone and subsequent effects on the way the kidney normally handles these salts. The salt changes, specifically a high blood potassium level, can have serious effects on the heart.

A definite diagnosis of Addison’s disease is made by your veterinary surgeon performing an ACTH stimulation test on your dog’s blood. This is a test where blood is taken, a drug (ACTH) is given to try and stimulate the adrenal gland and then a second blood test is taken one hour later. If the adrenal gland fails to respond to the drug, Addison’s disease is diagnosed.

What is the treatment for Addison’s disease?

The immediate treatment of life-threatening Addison’s disease involves the careful administration of fluids (‘a drip’) into the blood stream. Steroids are replaced by injection into the vein.

Once animals are stable they were traditionally gradually moved onto tablet medication. Most animals with Addison’s disease would have been discharged with prednisolone and fludrocortisone. Long term, the majority of animals were managed with fludrocortisone alone and this drug is given once or twice daily. The fludrocortisone dose often needs to be increased with time. In times of stress or illness (veterinary visits, bonfire night, boarding etc) animals will often need a dose of prednisolone in addition to their fludrocortisone and your veterinary surgeon will advise you on what to do in these situations.

Side effects of fludrocortisone can include increased drinking, increased urination, panting and muscle wastage.

Recently a new injectable medication (desoxycortisone pivalate) has become the first veterinary licensed product available for Addison’s disease and is used in place of fludrocortisone. It is intended for long term administration at intervals and doses dependent upon individual response as evaluated by regular blood tests.

What is the outlook for dogs with Addison’s disease?

Once animals are on appropriate therapy, they will require regular veterinary appointments for re-assessment and monitoring. The outlook for many dogs with Addison’s disease is very good with appropriate monitoring and treatment.