News

Special Offer – April 2017 – Tackling Ticks

by admin on April 1st, 2017

Category: Special Offers, Tags:

Pet of the Month – April 2017 – Diarmuid

by admin on April 1st, 2017

Category: Pet of the Month, Tags:

Distichiasis is a common condition in dogs. It occurs when eyelashes are abnormally positioned and emerge too close to the eyelid margin.

Distichiasis can occur in any breed of dog but is most commonly seen in the American Cocker and Cocker Spaniel, Miniature and Longhaired Dachshund, Bulldog and Weimeraner breeds.

What are the signs of distichiasis?

In many dogs the extra eyelashes do not cause a problem, but in some cases they can rub the surface of the eye and cause irritation. The most common signs that you will notice are increased blinking/squinting of the eye, increased watering, and redness of the ‘white’ of the eye.

What are the treatment options for distichiasis?

Distichiasis only requires treatment if the hairs are causing irritation, conjunctivitis or corneal ulceration. There are a number of treatment options:

- Ocular lubricants. In mild cases of distichiasis, daily use of a lubricating gel such as Viscotears, Geltears or Lacrilube may be sufficient to soften the hairs and reduce their irritation. Lifelong treatment will be required.

- Plucking. Sometimes the extra eyelashes can be plucked using special epilation forceps. This is particularly useful when there are only a few long hairs present. However, because the hairs will grow back after a few weeks, regular and lifelong treatment will be needed.

- Electrolysis. Under general anaesthesia, a fine electrode is inserted into each hair follicle and a current is applied to permanently destroy the hair follicle. Once the hair follicle is destroyed the distichia cannot regrow. However, because only those hairs that happen to be present at the time of treatment can be identified and removed, new hairs may emerge at a later date and also cause irritation. The success rate of electrolysis per treatment is around 70-80%. The procedure can be repeated a number of times if necessary. Rarely, electrolysis can cause some scarring and depigmentation of the eyelids, but this is not usually severe.

- Cryotherapy. This technique may be useful when many hairs are present. Under general anaesthesia, a probe is applied to the inner surface of the eyelid in the region of the hair follicles. Via this probe, the eyelid is frozen to destroy the hair follicles. The technique can cause some scarring and depigmentation of the eyelids. This procedure may also need to be repeated, and has a similar success rate to electolysis.

- Surgery. Excision of a very small portion of the eyelid margin from which the distichia are growing.

As the few distichia do not appear to be bothering Diarmuid’s eyes excessively, artificial tears are being used alone at present. Should the distichiasis become more of a problem then intervention along one of the lines described above will be necessary

Elbow Dysplasia in Dogs

by admin on March 1st, 2017

Category: News, Tags:

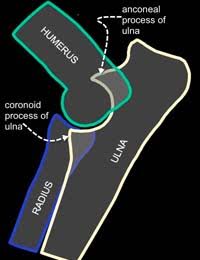

Osteochondrosis or osteochondritis dissecans(OC or OCD)

Osteochondrosis or osteochondritis dissecans(OC or OCD)- Fragmented coronoid process (FCP)

- Ununited anconeal process (UAP)

These conditions may be related to a poor fit between the three bones that make up the elbow joint. This poor fit or ‘incongruity’ can be seen on X-rays or by CT or MRI examination. In some patients, it may be difficult to identify because it is only present when the dog does certain activities, and sometimes this poor fit may have been present briefly during the dog’s development and is no longer present when investigations are performed.

These primary problems tend to develop when the puppy is only a few months of age and will commonly affect both elbow joints. Once a primary problem has started, secondary change soon follows. Secondary change takes the form of abnormal joint wear and arthritis. These secondary changes may have consequences for the rest of the dog’s life.

Are certain breeds prone to getting Elbow Dysplasia?

Elbow Dysplasia is a significant problem in many breeds worldwide. It is recognised in numerous breeds although large breeds seem to be most affected – particularly Labrador Retrievers, Newfoundlands, Golden Retrievers, Boxers, Rottweilers and German Shepherd Dogs. As investigation methods have improved we are increasingly recognising it in smaller breeds too.

Why do dogs get Elbow Dysplasia?

Elbow Dysplasia is a multifactorial disease which means that a number of factors influence its occurrence. Genetics plays an important role although the precise genetic basis of Elbow Dysplasia remains undetermined. Other factors that are thought to influence the disease include growth rate, diet, and level of activity.

How do I know if my pet has Elbow Dysplasia?

Not all dogs with Elbow Dysplasia will show obvious clinical signs of lameness. This may be because the condition is mild or because similar changes exist in both elbows which may mask the lameness. Clinically affected dogs with Elbow Dysplasia commonly show stiffness or lameness between 5 and 12 months of age. Typically owners describe that their dog is stiff after rest and after exercise but improves with light activity. Others will observe that their dog’s front feet begin to turn out. It is thought that this is an adaptation to elbow pain and is the dog’s way of relieving it.

What tests may be required?

Clinical examination may determine that the elbow joint is painful or swollen, although initially, the lameness may be difficult to localise to a particular joint. Confirmation of the diagnosis of Elbow Dysplasia is made by performing further investigations which would typically be X-rays or CT examination. X rays will often be able to determine whether your dog has elbow dysplasia either by identifying the primary problem or the osteoarthritis that occurs as a result. Three bones (humerus, radius, and ulna) combine to form the elbow joint and these overlap on radiographs. This makes identification of the primary lesion problematic in some cases.

Elbow radiographs and CT/MRI scans are important tests for detecting elbow dysplasia in dogs. CT/MRI examination is an excellent method of looking at the detailed structure of the joint and determining the precise nature of Elbow Dysplasia. It provides additional information to radiography and this can be useful when planning surgical treatments, especially in more complex cases.

Special Offer – March 2017 – Wellness Screen

by admin on March 1st, 2017

Category: Special Offers, Tags:

Pet of the Month – March 2017 – Prince

by admin on March 1st, 2017

Category: Pet of the Month, Tags:

Our pet of the month this March is a delightful and photogenic Pomeranian puppy called Prince.

Prince had to have his right foot X-rayed after he jumped off a bed and landed awkwardly. Unfortunately, in the process he fractured all the toes of his right paw and was unable to bear weight on it.

Following surgery to stabilise the fractures using small metal pins we are really pleased to report Prince is making good progress and hopefully will be back to normal very soon.

Special Offer – February 2017 – Neutering

by admin on February 1st, 2017

Category: Special Offers, Tags:

Pet of the Month – February 2017 – Hadley

by admin on February 1st, 2017

Category: Pet of the Month, Tags:

Hadley has featured in this column before and his return to this newsletter is to highlight the need for vigilance in respect of skin tumours. Hadley suffers from a very serious form of skin cancer called a Mast Cell Tumour (MCT), and he is recovering very well following surgery to remove yet another recurrence. MCT can be very deceptive as they often start as small bumps which may remain static for many months before growing larger. It can be extremely difficult to contain, frequently recurs and may be life threatening.

MCT is the most common skin tumour in dogs; it can also affect other areas of the body, including the spleen, liver, gastrointestinal tract, and bone marrow. MCT represent a cancer of a type of blood cell normally involved in the body’s response to allergens and inflammation. Certain dogs are predisposed to MCT, including brachycephalic (flat-faced) breeds such as Boston Terriers, Boxers, Pugs, and Bulldogs, as well as retriever breeds, though any breed of dog can develop MCT.

When they occur on the skin, MCT varies widely in appearance. They can be a raised lump or bump on or just under the skin, and may be red, ulcerated, or swollen. In addition, many owners will report a waxing and waning size of the tumour, which can occur spontaneously or can be produced by agitation of the tumour, causing degranulation. Mast cells contain granules filled with substances which can be released into the bloodstream and potentially cause systemic problems, including stomach ulceration and bleeding, swelling and redness at and around the tumour site, and potentially life-threatening complications, such as a dangerous drop in blood pressure and a systemic inflammatory response leading to shock.

When MCT occur on the skin, they can occur anywhere on the body. The biological behaviour of these tumours can vary widely; some may be present for many months without growing much, while others can appear suddenly and grow very quickly. The most common sites of MCT spread (metastasis) are the lymph nodes, spleen and liver.

Diagnosis can be simply achieved via a fine needle aspirate. This requires no anesthesia and only rarely sedation. Early identification and surgical removal are key to the most favourable outcomes however aggressive forms may require radical surgery and necessitate referral to a specialist cancer referral centre.

Hadley initially found the operation sites to be very itchy after surgery, something not uncommon with MCT. After removing a few of his own sutures Hadley was given additional medication, resutured and had to wear a full body suit! We are pleased to report he is making very good progress.

Head Tilt In Dogs

by admin on February 1st, 2017

Category: News, Tags:

What does it mean if my dog has a Head Tilt?

A persistent head tilt is a sign of a balance (vestibular) centre problem in dogs. It is very similar to ‘vertigo’ in people and is often accompanied by a ‘drunken’ walk and involuntary eye movements, either side to side or up and down.

The feeling that the room is spinning due to the eye movements is what causes a feeling of nausea in both people and dogs. The signs may not be as severe as mentioned here and can just consist of a mild head tilt. Signs often seen associated with a head tilt but unassociated with balance abnormalities include a facial ‘droop’ and deafness.

Causes of a head tilt

A head tilt represents a disorder of the balance centre. However, the balance centre resides in the inner bony portion of the ear as well as the brain. So a head tilt could represent a simple ear problem or a very serious brain disease.

Ear problems which are responsible for head tilts include:

- Infections

- Polyps

- Reactions to topical drops or solutions if the ear drum is damaged

- Hits to the head

- (Occasionally) ear tumours

- (Rarely) a genetic abnormality affecting puppies, especially those of the Doberman breed

- Idiopathic vestibular disease

The most common cause is what is called idiopathic vestibular disease. There is no known cause of this disease, a variant of which is also seen in people. The signs can start very suddenly and be accompanied by vomiting in severe cases. This condition, however, will resolve given time without any specific treatment.

Brain diseases responsible for balance centre dysfunction can include:

- Tumours

- Trauma

- Inflammation

- Stroke

- Rarely, similar signs can be seen in dogs that are receiving a specific antibiotic called metronidazole. Recovery will often take place within days of stopping this medication

Clinical signs of vestibular disease – is it the ear or is it the brain?

In addition to a head tilt, signs of vestibular disease (balance centre dysfunction) include ataxia (a drunken, falling gait) and nystagmus (involuntary eye movements). There are several signs to look for which help separate out whether the origin of the disease is inner ear or brainstem (Central Nervous system – CNS).

Central nervous system localisation will often be associated with weakness on one side of the body that can manifest as ‘scuffing’ or even dragging of the legs, in addition to lethargy, and sometimes problems eating and swallowing, or loss of muscle over the head.

A balance problem associated with an inner ear disease is not likely to be associated with any of these signs. However, some dogs will exhibit a droopy face and a small pupil on the same side as the head tilt.

Tests recommended for a dog with a head tilt

Evaluation of an animal with a head tilt includes physical and neurologic examinations, routine laboratory tests, and sometimes x-rays. Your veterinary surgeon may carry out a thorough inspection of the ear canal, which may require sedation of your dog – this can be useful to rule out obvious growths or infections. Additional tests may be recommended based on the results of these tests or if a metabolic or toxic cause is suspected. Identification of specific brain disorders requires imaging of the brain, such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Collection and examination of cerebrospinal fluid, which surrounds the brain, is often helpful in the diagnosis of certain inflammations or infections of the brain.

How do we treat head tilt in dogs

Treatment for vestibular dysfunction will focus on the underlying cause once a specific diagnosis has been made. Supportive care consists of administering drugs to reduce associated nausea and/or vomiting. Travel sickness drugs can be very effective. These must only be given following advice from your veterinary surgeon. Protected activity rather than restricted activity should be encouraged as this will potentially speed the improvement of the balance issues.

Outlook (prognosis) for head tilt in dogs

The prognosis depends on the underlying cause. The prognosis is good if the underlying disease can be resolved and guarded if it cannot be treated. The prognosis for animals with an idiopathic vestibular disease is usually good because the clinical signs can improve within a couple of months.

Myaesthenia Gravis in dogs

by admin on January 3rd, 2017

Category: News, Tags:

In this article, we will look at an important but quite rare cause of muscular weakness and collapse in dogs…Myasthenia Gravis.

What is myasthenia gravis?

Myasthenia Gravis (pronounced my-as-theen-ia grar-viss) is a possible cause of generalised weakness in dogs and occasionally cats. It also occurs in humans.

What happens in myasthenia gravis?

Nerves work like small electrical cables. They pass an electrical current into the muscles to make them contract or shorten. The nerve doesn’t directly stimulate the muscles to contract; instead, it releases a chemical into a small gap that exists between the end of the nerve and the outer lining of the muscle. This gap is called the neuromuscular junction. The chemical that is released is called a neurotransmitter and in most of our muscles this neurotransmitter is a chemical called acetylcholine. It is packaged into tiny pockets at the end of the nerve and it is released when a nerve impulse comes along.

In a fraction of a second the acetylcholine spurts out from the end of the nerve and sticks to the outer membrane of the muscle. This allows a small electrical current to flow into the muscle and the muscle contracts. To create this effect the acetylcholine must attach to a specific receptor on the muscle surface. This can be likened to a lock and a key opening a door. The lock is the receptor and the key is the acetylcholine. The two fit together perfectly and a microscopic door in the muscle wall then opens to allow the electrical current into the muscle cell. It has to be an exact fit so that the muscle only contracts when the nerve ‘tells’ it to.

In myasthenia gravis this chemical transmission across the neuromuscular junction becomes faulty and if the muscles are unable to contract properly they then become weak. Muscle weakness can affect the limbs so that animals are unable to stand or exercise normally but can also affect other muscles in the body. The muscles of the oesophagus (the pipe carrying food from the mouth to the stomach) are often weak in dogs with myasthenia gravis and this means that affected animals may have problems swallowing and often bring back food after eating.

What causes myasthenia gravis in dogs?

Some animals are born with too few acetylcholine receptors on the surface of their muscles i.e. it is a congenital disease. More commonly however, myasthenia gravis is an acquired condition that comes on later in life and here it is caused by a fault in the animal’s immune system.

Antibodies usually attack foreign material such as bacteria and viruses. In acquired myasthenia gravis, the immune system produces antibodies which attack and destroy the animal’s own acetylcholine receptors. No-one really knows why the immune system should suddenly decide to attack these receptors in some dogs. In rare cases, it can be triggered by cancer.

Whatever the reason, when the number of receptors is reduced, acetylcholine cannot fix itself to the muscle to produce normal muscle contractions and muscle weakness results.

How do I know if my pet has myasthenia gravis?

The typical picture is a severe weakness after only a few minutes of exercise. This weakness might affect all four legs or only affect the back legs. It is frequently preceded by a short stride, stiff gait with muscle tremors. The patient eventually has to lie down. After a short rest they regain their strength and can be active again for a brief period before the exercise-induced weakness returns. Other signs of myasthenia are related to effects on the muscles in the throat and include regurgitation of food and water, excessive drooling, difficulty swallowing, laboured breathing and voice change. In the most severe form, the animal can be totally floppy and unable to support its weight or hold its head up.

Which dog and cat breeds are most commonly affected?

The acquired form is seen most commonly in Akitas, terrier breeds, German Shorthaired Pointers, German Shepherd Dogs and Golden Retrievers. In cats it is Abyssinians and a close relative, Somalis. The rare congenital form has been described in Jack Russell Terriers, Springer Spaniels and Smooth-haired Fox Terriers.

What conditions can it be confused with?

Diseases of the muscles (a myopathy) or nerve disease (a neuropathy) can mimic signs of myasthenia gravis and should be considered in the diagnosis.

How is myasthenia gravis diagnosed?

Your vet will often be very suspicious based on the clinical signs and medical history alone. A blood test can be performed to detect antibodies directed toward the acetylcholine receptor. Another test that is sometimes performed is known as the ‘Tensilon test’. Here the patient is given a short-acting antidote that boosts the effects of acetylcholine on the muscle. It is injected into a vein and in patients that have myasthenia gravis there will be a dramatic increase in muscle strength immediately after injection and collapsed animals may get up and run about. However, the effects wear off after a few minutes.

In specialist centres an electromyogram (EMG) may be performed. An EMG machine can be used to deliver a small electrical stimulation to an individual nerve or muscle in an anaesthetised animal. Using an EMG machine we can measure how well the muscles respond to stimulation.

The rare congenital form of myasthenia is usually diagnosed by special analysis of a muscle biopsy.

Chest X-Rays will also be performed to look for cancer in the chest cavity which can trigger myasthenia gravis. The chest x rays will also help to evaluate possible involvement of the oesophagus and to detect pneumonia secondary to inhalation of food.

Can myasthenia gravis be treated?

Specific treatment of myasthenia gravis is based on giving a long-acting form of a drug that works like the Tensilon in the test described above. These chemicals boost the effects of acetylcholine on the muscle cells and improve the transfer of the electrical signal from the nerves to the muscles. It may also be necessary to give drugs that will suppress the immune system to stop it attacking the acetylcholine receptors. This will make the patient more susceptible to infections and so they would require careful monitoring whilst on immunosuppressive drugs, particularly with the increased risks of pneumonia is myasthenia patients.

What is the outlook for dogs and cats with myasthenia gravis?

The outlook is generally good unless the patient develops a secondary severe pneumonia due to the inhalation of food material. Treatment usually lasts many months and your vet will need to re-examine your pet on a regular basis to check that they are improving. Repeated blood tests to measure the levels of the antibodies against the acetylcholine receptors will also be required.

Myasthenia gravis is a serious and very debilitating disease. However, with an early diagnosis and a high level of care the symptoms may be controlled so that your pet has an active life. Some patients may make a full recovery.

Pet of the Month – January 2017 – Sophia

by admin on January 3rd, 2017

Category: Pet of the Month, Tags:

Pet of the month for January is Sophia, an 11-year-old Pug. She is seen here in post-op recovery having just had an ovariohysterectomy to treat a condition called pyometra.

Pet of the month for January is Sophia, an 11-year-old Pug. She is seen here in post-op recovery having just had an ovariohysterectomy to treat a condition called pyometra.

Pyometra is an infection of the uterus (womb). It is a common condition in older female dogs that have not been spayed but can occur in un-spayed dogs of any age. Occasionally we see cases occurring in cats.

What causes pyometra?

Each time a female dog has a season (usually about twice a year) she undergoes all the hormonal changes associated with pregnancy – whether she becomes pregnant or not. The changes in the uterus that occur during each season making infection more likely with age. A very common organism called E. coli, found in your dog’s faeces, usually causes the infection. We most commonly see cases of pyometra in the 4-6week period after a heat. Injections with some hormones to stop seasons or for the treatment of other conditions can also increase the risk of pyometra developing.

What are the signs of pyometra?

Pyometra is of course, only seen in females (since males do not have a uterus). It is more common in older females (above 6 years of age) but can be seen at any age. The signs usually develop around 6 weeks after the female has finished bleeding from her last season, but in some cases, the bitch appears to have a prolonged season.

Early signs that you may notice are that your dog is:

- Licking her back end more than normal

- Off colour

- Off her food

- Drinking more than normal (and will probably urinate more)

These signs will progress and you may see:

- Pus (yellow/red/brown discharge) from her vulva

- She may have a swollen abdomen

- Vomiting

- Collapse

If left untreated signs will worsen to the point of dehydration, collapse and death from septic shock.

Diagnosis

Your vet will probably suspect your dog has a pyometra based on your description of the signs and from their examination of your pet. They may suggest procedures such as ultrasound and blood tests confirm the diagnosis, rule out other possible causes and to check that your pet is well enough to undergo treatment.

Treatment

The treatment of choice for pyometra is surgery to remove the uterus as soon as possible. The operation is essentially the same as a routine spay, however, there is more risk involved and a higher chance of complications when the operation is being carried out on a sick pet. Your dog will also be given intravenous fluids (a drip), antibiotics and pain relief.

Most dogs will make a full recovery after treatment for a pyometra if the condition is caught early. Spaying your dog before she develops a pyometra will prevent this condition occurring.

We are delighted to report that Sophia has made a full recovery after surgery.