News

Pet of the Month – July 2017 – Henry

by admin on July 4th, 2017

Category: Pet of the Month, Tags:

Our pet of the month is Henry who we are pleased to say has recovered fully from a severe bout of pancreatitis, which necessitated a period of hospitalisation.

What is pancreatitis?

The pancreas is an organ in the abdomen (tummy) which is responsible for releasing enzymes (types of proteins) to digest food. The pancreas also releases important hormones (such as insulin) into the bloodstream. Pancreatitis occurs when the pancreas becomes inflamed (tender and swollen). In most cases pancreatitis occurs for no apparent underlying reason, although sometimes it can have a particular cause (such as scavenging food). Pancreatitis most commonly affects middle aged to older dogs, but in addition, dogs of certain breeds (e.g. Cocker Spaniels and Terrier breeds) are more prone to developing the condition.

What are the signs of pancreatitis?

Pancreatitis can cause a variety of symptoms, ranging from relatively mild signs (e.g. a reduced appetite) to very severe illness (e.g. multiple organ failure). The most common symptoms of pancreatitis include lethargy, loss of appetite, vomiting, abdominal pain (highlighted by restlessness and discomfort) and diarrhoea.

How is pancreatitis diagnosed?

The possibility that a dog may be suffering from pancreatitis is generally suspected on the basis of the history (e.g. loss of appetite, vomiting) and the finding of abdominal pain on examination by the veterinary surgeon. Because many other diseases can cause these symptoms, both blood tests and an ultrasound scan of the abdomen are necessary to rule out other conditions and to reach a diagnosis of pancreatitis. Although routine blood tests can lead to a suspicion of pancreatitis, a specific blood test (called ‘canine pancreatic lipase’) needs to be performed to more fully support the diagnosis. An ultrasound scan is very important in making a diagnosis of pancreatitis. In addition, an ultrasound scan can also reveal some potential complications associated with pancreatitis (e.g. blockage of the bile duct from the liver as it runs through the pancreas).

How is pancreatitis treated?

There is no specific cure for pancreatitis, but fortunately, most dogs recover with appropriate supportive treatment. Supportive measures include giving an intravenous drip (to provide the body with necessary fluid and salts) and the use of medications which combat nausea and pain. Most dogs with pancreatitis need to be hospitalised to provide treatment and to undertake necessary monitoring, but patients can sometimes be managed with medication at home if the signs are not particularly severe. At the other extreme, dogs that are very severely affected by pancreatitis need to be given intensive care.

One of the most important aspects of treating pancreatitis is to ensure that the patient receives sufficient appropriate nutrition while the condition is brought under control. This can be very difficult because pancreatitis causes a loss of appetite. In this situation, it may be necessary to place a feeding tube which is passed into the stomach, and through which nutrition can be provided (see Information Sheet on Feeding Tubes). If a dog with pancreatitis is not eating and will not tolerate a feeding tube (e.g. due to vomiting), intravenous feeding (using a drip to supply specially formulated nutrients straight into the bloodstream) may be necessary.

What is the outcome in pancreatitis?

It may be necessary for dogs with pancreatitis to be hospitalised for several days, but fortunately, most patients with the condition go on to make a complete recovery, provided that appropriate veterinary and nursing care is provided. In some instances, dogs can suffer repeated bouts of the condition (called ‘chronic pancreatitis’) and this may require long term management with dietary manipulation at the forefront.

Disc Disease in Dogs

by admin on July 4th, 2017

Category: News, Tags:

Dachshunds and similar breeds such Pekingese, Lhasa Apsos and Shih Tzus, have short legs and a relatively long back. These breeds suffer from a condition called ‘chondrodystropic dwarfism’. As a result they can be prone to back problems, more specifically disc disease.

What are intervertebral discs?

The intervertebral disc is a structure that sits between the bones in the back (the vertebra) and acts as a shock absorber. The structure of a disc is a little like a jam doughnut with a tough fibrous outer layer (annulus fibrosus) like the dough, and a liquid/jelly inner layer (nucleus pulposus) like the jam.

In chondrodystrophoid breeds like dachshunds, the discs undergo change where the nucleus pulposus changes from a jelly-like substance into cartilage. Sometimes the cartilage can mineralise and become more like bone and show up on an x-ray. In these breeds, this change occurs in all discs from approximately one year of age and is considered part of usual development for these dogs. This change in the discs is a degenerative process and predisposes the disc to disease.

The most common type of disc disease in dachshunds and other chondrodystrophoid breeds is ‘extrusion’. This is where the annulus fibrosus ruptures and allows the leakage of the nucleus pulposus into the spinal canal. An analogy we often use is the jam leaking from a jam doughnut when it is squeezed.

What are the signs of disc disease in dachshunds and other breeds?

The first evidence that there might be a problem is that your dog may be in pain. This may consist of yelping and/or a hunched back and more subtle signs such as quietness and inappetence (lack of appetite). Back pain is commonly mistaken for abdominal pain.

After pain there may be mobility problems. The first thing to occur is wobbliness of the hind limbs – termed ‘ataxia’. After this, weakness can develop with the wobbliness, which is termed paresis. Subsequently, the patient may lose control of the back legs altogether and not be able to walk. If there is no movement in the hind limbs this is ‘paralysis’.

Will my dog need to be referred to a specialist?

Spinal disease can sometimes be difficult to manage and your dog may be referred to a specialist. At the referral clinic, your dog will be assessed by the specialist neurologist or neurosurgeon. They will test various reflexes to decide where they think the issue may be. They will perform a clinical examination which will assess for other disease processes and look for any areas of pain. One thing that is important to assess is the presence of pain sensation. We call this ‘deep pain sensation’. To assess this, the specialist will pinch your dog’s toes, usually with fingers initially but it may need to be with forceps. This is not a pleasant test to perform but it is necessary as the presence of deep pain comes with a more favourable prognosis. The loss of deep pain sensation means the prognosis is worse and without surgery is considered very poor.

What investigations will be performed?

After the clinical examination, we will generally have a good idea where the problem is and the next step is to confirm the diagnosis. The best way of diagnosing disc disease is with MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) or CT (computed tomography). With MRI we get detailed information about the soft tissue such as the disc itself and the spinal cord. Computed tomography uses the same technology as x-ray and provides good information about the bone and mineral structures and can tell us where the lesion is and whether or not surgery is indicated.

How is disc extrusion treated?

If a disc extrusion – the ‘jam out of the doughnut’ scenario – is diagnosed then we can opt for conservative care or surgical management.

Conservative care is a non-surgical management and can be considered in dogs where the signs are mild or intermittent and when there is only mild compression of the spinal cord. It can also be considered if there are concerns regarding the cost of surgery.

Surgical treatment involves making a window through the bone structures of the vertebra, into the spinal canal, a procedure called a ‘hemilaminectomy’. Once into the spinal canal, the disc material (nucleus pulposus) is removed and the spinal cord is decompressed. Surgical treatment tends to give a speedier and more predictable recovery and is often considered the treatment of choice, where indicated.

What is the prognosis for a dog with disc disease?

When dealing with spinal injury, particularly from disc disease, we aim for patients to achieve a functional recovery. This means the patient is pain free, is able to get around on their own (although they may still be wobbly) and able to toilet themselves unaided. Whether a patient will return to normal or whether there will be residual deficits is down to the individual.

The prognosis for patients who have intact deep pain sensation is favourable, with most patients (80-90%) achieving a functional recovery. In patients without deep pain sensation, the prognosis is guarded, with only 50% of cases achieving a functional recovery but without surgery the prognosis for a functional recovery is approximately 5%.

Surgery tends to speed recovery and aid early pain control. We expect most patients to recover within the first 2 weeks after surgery, with a smaller number of patients taking longer (2-6 weeks). If there is no improvement after 6 weeks the prognosis becomes more uncertain and long term disability may be present. This occurs in approximately 1 in 10 patients.

Pet of the Month – June 2017 – Louie

by admin on June 1st, 2017

Category: Pet of the Month, Tags:

This June our Pet of the Month is Louie.

Almost 3 years ago he was discovered to have Atrioventricular Insufficiency (AVVI) during a routine investigation for an episode of acute pain, and has been managing very well since that time with appropriate medication.

Overview

AVVI is a degenerative disease that damages heart valve leaflets as it progresses. This damage prevents heart valves from closing properly, allowing blood to leak backward into the atrium. This leakage eventually results in a heart murmur detectable via auscultation with a stethoscope. Valve leakage impairs cardiac function and circulation, ultimately leading to congestive heart failure (CHF).

Estimates indicate that 10% of all dogs seen in primary care veterinary practices have heart disease. As dogs age, the prevalence of heart disease reaches more than 60%.

AVVI, the most frequent cause of CHF in dogs, is a slowly progressing disease. The prevalence of this disease gradually increases with age. AVVI affects:

- 10% of dogs 5 to 8 years of age

- 20% to 25% of dogs 9 to 12 years of age

- 30% to 35% of dogs over age 13 years

This increase is especially dramatic in small breeds, with up to 85% showing evidence of valvular lesions by 13 years of age.

Video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?

AVVI occurs most often in small- to medium-sized breeds of dogs. Breeds most susceptible to AVVI include the Boston Terrier, Cavalier King Charles Spaniel, Chihuahua, Miniature Pinscher, Miniature and Toy Poodle, Pekingese, and Pomeranian. Ultimately, all small breed dogs are at risk for CHF due to AVVI.

Management

When it comes to managing canine congestive heart failure (CHF) with the goal of improving and extending life, time matters. Though the early stages of heart disease can progress slowly, once clinical signs appear, immediate treatment is needed.

In fact results of recent longterm studies show that the early administration of appropriate medication to dogs with mitral valve disease who have echocardiographic and radiographic evidence of cardiomegaly (heart enlargement) results in prolongation of the preclinical period (period before any illness is evident) by approximately 15 months, which represents substantial clinical benefit.

Special Offer – June 2017 – Microchip Offer

by admin on May 30th, 2017

Category: Special Offers, Tags:

Mycoplasma in Poultry

by admin on May 30th, 2017

Category: News, Tags:

The ‘Head Cold’ of the Poultry World

As more and more pet owners are keeping poultry we felt it appropriate to look at one of the most common infections that may be seen.

The main culprit of Mycoplasma infection in backyard poultry is Mycoplasma gallisepticum. This is one of the organisms that makes up the colloquially-termed ‘chronic respiratory disease syndrome’ (potentially in association with Infectious Laryngotracheitis) in poultry worldwide. It is considered to be responsible for some of the greatest economic losses throughout commercial flocks around the globe, but can just as easily impact on smaller backyard flocks.

Who catches Mycoplasma, and how?

Poultry, including chickens and turkeys, are most often presented with respiratory issues involving Mycoplasma gallisepticum, but a wide range of other birds including pheasants and wildfowl can be affected.

Mycoplasma gallisepticum can be spread vertically (from hen to egg) leading to infected chicks, or, and perhaps more commonly, through horizontal transmission (bird to bird). The disease can be spread short distances through the air as an aerosol, or on shoes/water drinkers/feeders. The disease itself may remain dormant within the infected bird for potentially months before causing any overt clinical disease. It is often at this stage that rapid spread of the disease occurs throughout a flock.

What does Mycoplasma in poultry look like?

Focusing on the presenting signs of poultry, the degree of clinical signs can vary widely from no apparent signs up to the potential death of the bird in more aggressive, complicated disease development.

The more common presenting signs can include:

- Rales (clicking, rattling, or crackling noises)

- Coughing

- Nasal discharge

- Discharge from around the eyes

- Swelling under the eyes

In more advanced cases, sinusitis may become apparent.

There may also be more generic signs of illness present including the birds appearing fluffed up, off food, keeping themselves away from the rest of the flock and reduction in egg production or going off lay completely.

Clinical signs are often quicker to develop and more severe in turkeys than chickens.

Can Mycoplasma in poultry be treated?

Mild to moderate disease can be treated successfully with appropriate antibiotics prescribed by your vet, pain relief and good nursing management (TLC!). It is important to note however that once your bird/flock has suffered from the disease, it likely to circulate and be present from thereon in. This becomes an important factor when either bringing in new birds or selling/moving your own birds.

Chickens, as well as most other birds, will suffer a much more marked immune ‘crash’ when stressed in comparison to other animals. This means that when birds are moved to a new location or mixed with other birds, the stress can induce a marked reduction in their active immunity causing a rapid onset of disease symptoms (sneezing, coughing, etc.).

Due to the risk of disease spread amongst new birds, it is absolutely vital to quarantine any incoming birds for at least 3-4 weeks to ensure that you are not putting your own birds at risk of disease.

Prevention is better than cure!

Vaccinations are available against certain strains, but use of a vaccine must be with caution as quarantine procedures would still always be advised, and any new birds bought in would have to have been vaccinated. The danger with vaccinating poultry is that all too often it is seen as an easily-achievable blanket cover for disease. Good biosecurity, involving washing boots, is important. Always thoroughly disinfect items that are brought in or taken off the holding containing your particular birds.

Pet of the Month – May 2017 – Bob

by admin on May 1st, 2017

Category: Pet of the Month, Tags:

Bob is one of many cats we attend who suffers from IBD (Inflammatory Bowel Disease).

IBD is not a single disease but a group of chronic gastrointestinal disorders caused by an infiltration of inflammatory cells into the walls of a cat’s gastrointestinal tract. The infiltration of cells thickens the wall of the gastrointestinal tract and disrupts the intestine’s ability to function properly. IBD occurs most often in middle-aged and older cats.

How is IBD diagnosed?

Symptoms of feline IBD are not specific. They may include vomiting, weight loss, diarrhea, lethargy and variable appetite. The symptoms of IBD can vary depending on the area of the digestive tract affected.A definitive diagnosis of feline IBD can only be made based on a microscopical evaluation of tissue collected by means of an intestinal (or gastric) biopsy.

How is IBD treated?

The treatment of IBD usually involves a combination of change in diet and the use of various medications. There is no single best treatment for IBD in cats. Your veterinarian may need to try several different combinations to determine the best therapy for your cat.

Hypoallergenic diets are usually tried first. Corticosteroids like prednisolone may be used to reduce inflammation of the gut. Antibiotics such as metronidazole are commonly used.

What does the future hold for a cat with IBD?

IBD is a chronic disease. Few cats are actually cured. Symptoms of IBD may wax and wane over time. IBD can often be controlled such that affected cats are healthy and comfortable. Vigilant monitoring by the veterinarian and owner is critical.

We are very pleased to report that Bob has responded well to dietary management and is currently not requiring additional medication. Luckily he is not adept at hunting and so we have no fear that he might upset the illness through illicit snacks!

Brachycephalic Obstructive Airway Syndrome (BOAS)

by admin on May 1st, 2017

Category: News, Tags:

‘BAOS: Too much soft tissue and not enough space’

Brachycephalic breeds are those with squashed up faces! We love them and they are great characters but selective breeding over many generations has encouraged the skull to be progressively shorter over time. However, the amount of soft tissue in the nose and throat has remained the same. These soft tissues include the soft palate, turbinates (cartilage inside the nose) and tongue. These are all crammed into a smaller space. In addition, a lack of underlying nasal bones also causes the nostrils to become very narrow appearing like small slits instead of open holes.

Breathing problems

The crowding of this tissue inside the nose and the back of the throat obstructs airflow through the upper airways. This is why many of these dogs are forced to breathe through their mouth and pant. In an attempt to draw air in through this cramped space many affected dogs will put much more effort into their breathing. This is why if you watch these patients closely you will see them using their abdominal muscles as bellows during breathing. A good analogy for this is comparing how difficult it would be to suck through a very narrow straw compared to a normal one.

The ‘knock-on’ effects of laboured breathing

Unfortunately, the increased effort creates a suction effect in the back of the throat at the opening into the trachea (windpipe). This opening into the windpipe is called the larynx (or voice box in people). It has a tough cartilage frame which keeps it open wide. However, constant suction in this region over a period of months can cause it to fold inwards further narrowing the airway and causing serious breathing difficulty. This secondary problem is called laryngeal collapse.

What about the nose?

The nose is an important part of the anatomy and it functions to warm and humidify the air before it is inhaled into the lungs. It is a crucial part of how dogs maintain a normal body temperature. If affected dogs can’t breathe through their nose then this significantly affects their ability to thermoregulate and explains why they have poor heat tolerance. Of course, it is no surprise that many patients present with breathing problems in the summer months.

What are the clinical signs of Brachycephalic Obstructive Airway Syndrome (BOAS)?

The main clinical signs in approximately increasing the order of concern include:

- Loud snoring during sleep

- Noisy breathing (especially during excitement or exercise)

- Panting

- Poor ability to exercise

- Heat intolerance

- Choking on food

- Regurgitating

- Laboured breathing

- Development of blue gums or tongue

- Fainting

Aren’t some of these signs just ‘Normal’ for the breeds?

Yes and no. The problem is that a large number of brachycephalic dogs show the signs at the milder end of the above spectrum and our tolerance of what is normal for these breeds has become skewed. We frequently see patients coming into our clinic for unrelated problems with marked breathing difficulty. When questioned their owners often state that they consider these signs as normal for the breed. They often add that most other dogs of the same breed that they come across on walks sound and react the same which reinforces this notion! Therefore it is important that we get the message across that these signs are abnormal and if your dog is displaying some of them then a veterinary opinion should be sought.

Be proactive!

A proactive approach is beneficial as there are many surgical treatments which can be carried out that will help these patients breathe. Although these treatments will not produce a ‘normal’ airway it will invariably improve airflow, thus improving their quality of life and ability to exercise. The latter is particularly important as obesity makes this problem significantly worse. Intervention early in life can reduce the amount of suction at the back of the throat and therefore reduce or delay the development of secondary laryngeal collapse for which there are limited options available.

See the excellent new film on BAOS by the Kennel Club on Youtube entitled ‘Dog Health: What Is Brachycephalic Obstructive Airway Syndrome?’

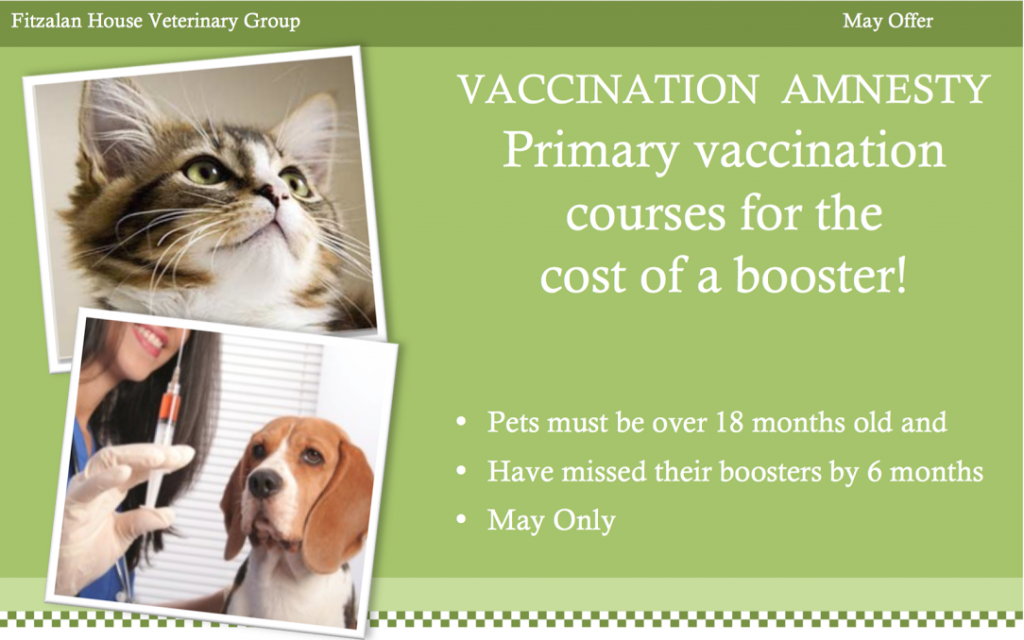

Special Offer – May 2017 – Vaccine Amnesty

by admin on May 1st, 2017

Category: Special Offers, Tags:

Epilepsy in Dogs

by admin on April 1st, 2017

Category: News, Tags:

Epilepsy means repeated or recurrent seizures or “fits” due to abnormal activity in the brain. Electrical activity is happening in the brain all the time however in some patients an additional and abnormal burst of electrical activity can occur which causes a fit. Some dogs will just have one fit but in others it becomes a regular event – this is Epilepsy. It is important to realise that Epilepsy is not a disease in itself but the sign of an abnormal brain function. The most commonly diagnosed form of epilepsy is referred to as Primary Epilepsy and is more common in certain breeds. Epilepsy does occur in cats but is much less common.

Are all fits the same?

No and as It is very likely your vet won’t see the fit taking a short video can be extremely helpful to them in deciding on the best course of action. Many types of seizure have been described in dogs and cats. The most common type is the grand mal which is the dramatic, typical fit where the patient lies on the floor and the whole body twitches and convulses rhythmically. Partial epileptic seizures that affect only one part of the body can also occur. These are less common and can be difficult to differentiate from other unusual non-epileptic movement disorders.

The seizure frequency is extremely variable between dogs (from many seizures a day to a seizure every few months). Despite being born with this functional brain disorder, dogs with primary epilepsy usually do not start seizuring before the age range of 6 months to 6 years. In the absence of disease affecting the brain, animals are typically normal in between the epileptic seizures.

What causes epilepsy?

The exact mechanism is unknown but in many cases the tendency to develop epilepsy is thought to be passed on genetically. In Primary epilepsy there is no obviously abnormal brain tissue and it is due to a chemical imbalance or to some ‘faulty wiring’ in the brain.

What is Secondary Epilepsy?

Secondary epilepsy is when the fits are being caused by another brain disorder such a brain tumour, an inflammation or infection of the brain (encephalitis), a brain malformation, a recent or previous stroke or head trauma. In other words there is an identifiable cause for the regular fits and there is some structurally abnormal brain tissue.

How is Epilepsy diagnosed?

The diagnosis of primary epilepsy is unfortunately a diagnosis of exclusion after elimination of other causes. There is no definitive diagnostic test for this condition and all investigations such as blood tests, brain scans and laboratory analysis of the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), which surrounds the brain and spinal cord, will all come back as completely normal!

Can you cure epilepsy?

Primary Epilepsy is unfortunately a condition that the animal is born with and as such it cannot be cured. Using anti-epileptic medication such as phenobarbitone will prevent some patients having any more fits. Although complete control is the goal of treatment, in most circumstances ‘successful treatment’ is a balancing act of reducing the frequency and severity of the seizures to a low level whilst avoiding unacceptable side effects of the drugs. So a patient may still have some fits despite being on treatment.

When should medication be started?

This isn’t a black and white issue. A substantial number of dogs will only have one fit in their entire lifetime and so if every dog was started on treatment after its first fit then all these dogs would be receiving medication unnecessarily. However, there is some evidence to suggest that early treatment offers better long-term control of the seizures as compared to animals that are allowed to have numerous seizures prior to the onset of treatment. We also have to take into account that anti-epileptic medications can have side effects and getting things under control will often place significant demands on you as the pet owner and carer.