News

Lymphoma in Dogs

by admin on November 1st, 2017

Category: News, Tags:

What is lymphoma?

Lymphoma is a cancer of the lymphatic system. The lymphatic system is, amongst other things, involved in immunity and fighting infections. Lymphoma arises from cells in the lymphatic system called lymphocytes which normally travel around the body, so this form of cancer is usually widespread. Lymph nodes (sometimes called lymph glands) are part of the lymphatic system and are located all over the body. Lymphoma can affect some or all of the lymph nodes at the same time. It may be possible to feel or see affected lymph nodes that are near the body surface (as shown in the picture) – they usually feel big and firm. Lymph nodes deeper inside the body are also often involved, as well as internal organs such as the liver, spleen, and bone marrow. This widespread involvement is not like tumour spread in other types of cancer.

Lymph nodes you can feel:

1 Submandibular: under the jaw

2 Prescapular: in front of the shoulder

3 Axillary: in the armpit

4 Inguinal: in the groin

5 Popliteal: behind the knee

What tests will my dog have?

The diagnosis of lymphoma is usually confirmed by taking a sample from a lymph node, either by fine needle aspirate or biopsy. Fine needle aspirate of a superficial lymph node is a quick, simple procedure using a needle (similar to those used for booster injections) to collect cells from the node. It causes minimal discomfort and is normally carried out while a patient is awake or under mild sedation. In some cases we need to take a biopsy, involving the removal of a larger sample of tissue – this may be carried out under a general anaesthetic. These tests allow a very accurate assessment of the tumour by a specialist looking at the samples under a microscope.

To allow evaluation of internal lymph nodes and organs, patients usually have X-rays and an ultrasound scan. Mild sedation is usually required for these procedures, as we need our patients to be very still. Blood sampling is also performed to assess a patient’s general health status.

In some cases we will recommend taking samples of bone marrow to investigate whether or not cancer cells are present in the bone marrow. This procedure is carried out under a short general anaesthetic.

All the diagnostic information we obtain allows us to give an accurate prognosis and to discuss appropriate treatment options.

Can lymphoma be treated?

The simple answer is yes. It is very uncommon for lymphoma to be cured, but treatment can make your dog feel well again for a period of time, with minimal side effects. This is called disease remission, when the lymphoma is not completely eliminated but is not present at detectable levels.

Without treatment, survival times for dogs with lymphoma are variable, depending on the tumour type and extent of the disease, but for the most common type of lymphoma the average survival time without treatment is 4 to 6 weeks. With current chemotherapy regimes such as the so-called Madison Wisconsin protocol, the average survival time is approximately 12 months.

Treatment options will be discussed in detail on an individual patient basis. Options include:

Steroid treatment (Prednisolone):

By itself, this increases average survival times to 1 to 3 months, but it does not work in all cases. It will also make subsequent treatment with chemotherapy less successful.

Chemotherapy:

using medications to stop or hinder cancer cells in the process of growth and division.

What does chemotherapy involve?

On each treatment day, before receiving chemotherapy, your pet’s progress is discussed, together with us performing a full physical examination and blood tests. Following this assessment, chemotherapy doses are calculated and the drugs are administered either subcutaneously (under the skin), intravenously (into a vein) via a catheter, or orally.

Chemotherapy with the Madison Wisconsin protocol involves your pet having chemotherapy treatments weekly for nine weeks (with a one week break), then fortnightly up until 6 months (i.e. 25 weeks in total). At 6 months, if your dog is in remission, therapy will be discontinued. Chemotherapy can be restarted when a patient relapses i.e. when lymphoma comes back. Patients are individuals, so the response varies from case to case, and because of this, all patients receiving chemotherapy are carefully monitored and protocols adjusted to suit the individual.

What are the potential side effects of chemotherapy and how can they be minimised?

Side effects can be seen because chemotherapy agents damage both cancer and normal rapidly dividing cells. Normal tissues that are typically affected include the cells of the intestine, bone marrow (which makes the red blood cells, white blood cells and cell fragments involved in blood clotting called platelets) and hair follicles. Hair loss is uncommon in dogs having chemotherapy, but it can be seen in certain breeds that have a continuously growing coat, such as Poodles and Old English Sheepdogs (cats rarely develop hair loss, but may lose their whiskers). Hair usually grows back once chemotherapy is discontinued. Damage to the cells of the intestines can result in changes in appetite or stool consistency and occasionally vomiting. Damage to the bone marrow reduces blood cell production, particularly infection fighting white blood cells (neutrophils).

Steroids are often used in combination with chemotherapy. These medications can make patients feel that they want to eat and drink more (especially during the first week of therapy when doses are usually higher and given every day). Patients should not have their access to drinking water restricted, but it is important not to increase their food intake, as excess weight gain can be problematic. The increased thirst is associated with increased urination, so patients may also need to go out to pass urine more often.

Cyclophosphamide, one of the commonly used chemotherapy agents, can cause irritation to the lining of the bladder, producing cystitis-like signs, so it’s important to bring urine samples when requested and to monitor your pet’s urination very carefully, and to promptly report any signs of problems.

Epirubicin, another chemotherapy agent, can cause damage to the heart muscle over time. The more doses your dog has, the greater the risk. For this reason, we will carry out checks on the heart before the drug is given for the first time and at various points during the treatment course. Heart complications are extremely uncommon and your dog is at much greater risk if the lymphoma is not treated.

We prescribe medications to help to prevent complications, and we will advise you on which signs to monitor. Compared to human patients who receive chemotherapy, pets experience fewer and less severe side effects, and these can usually be managed at home. This is because we use lower drug doses and do not combine as many drugs as in human medicine. Your pet’s quality of life is really important to us and to you.

What precautions do I need to take at home, with my pet having chemotherapy?

Chemotherapy agents can be excreted in the urine and faeces, and care must be taken when handling your pet’s waste. You will be advised of appropriate precautions, and it is important to note explicitly that pregnant women should avoid contact with the pet’s waste following chemotherapy.

What should I look out for?

Signs of gastrointestinal upset: if your pet has vomiting or diarrhoea for more than 24 hours please contact us or your usual vet. Also watch for any dark coloured faeces.

Signs of bone marrow suppression: Neutrophils (infection fighting white blood cells) are at their lowest point usually 5 to 7 days after treatment. If your pet is depressed, off its food, panting excessively or is hot to the touch at this time, please contact us.

Signs of bladder problems: you should alert us if your dog is urinating more frequently than he or she has been, is straining or having difficulty passing urine, or if you see blood in the urine.

What will happen in the future?

Unfortunately, chemotherapy for lymphoma is very unlikely to cure your pet, but will allow a good quality of life to be enjoyed for some time.

Inevitably, the cancer cells become resistant to the drugs we use, and the cancer will come back. At this stage, it is often possible to get the cancer back under control for a while with alternative agents (this is known as a ‘rescue’ treatment). Eventually, the tumour cells will become resistant again and it is likely that your pet will have to be put to sleep when his or her quality of life deteriorates.

Hopefully, this will be after many happy months of good quality life for your pet and you to enjoy together.

Canine Mast Cell Tumours

by admin on October 4th, 2017

Category: News, Tags:

Mast cells are normal cells found in most organs and tissues of the body, and are present in highest numbers in locations that interface with the outside world, such as the skin, the lungs and the gastrointestinal tract (stomach and bowels). They contain granules of a chemical called histamine which is important in the normal response of inflammation. When mast cells undergo malignant transformation (become cancerous), mast cell tumours (MCTs) are formed. Mast cell tumours range from being relatively benign and readily cured by surgery, through to showing aggressive and much more serious spread through the body. Ongoing improvements in the understanding of this common disease will hopefully result in better outcomes in dogs with MCTs.

Why do dogs get Mast Cell Tumours (MCTs)?

This is unknown, but as with most cancers is probably due to a number of factors. Some breeds of dog are predisposed to the condition, and this probably suggests an underlying genetic component. Up to 50% of dogs also have a genetic mutation in a protein (a so-called receptor tyrosine kinase protein) which inappropriately drives the progression of mast cell cancer cells.

The role of these receptor tyrosine kinases in canine MCTs is very interesting and also important in understanding the role and mechanisms of the newer drugs available for treating canine MCTs: the tyrosine kinase inhibitors (see Treatment Options).

Where in the body do MCTs occur?

The vast majority of canine MCTs occur in the skin (cutaneous) or just underneath the skin (subcutaneous). In addition, they are occasionally reported in other sites, including the conjunctiva (which lines the eyeball and eyelids), the salivary glands, the lining of the mouth and throat, the gastrointestinal tract, the urethra (the tube from the bladder), the eye socket and the spine.

Breed predisposition

Some breeds of dog are predisposed to getting mast cell tumours, amongst them are:

- Australian Cattle Dog

- Beagle

- Boston Terrier

- Boxer

- Bull Terrier

- Bullmastiff

- Cocker Spaniel

- Dachshund

- English Bulldog

- Fox Terrier

- Golden Retriever

- Labrador Retriever

- Pug

- Rhodesian Ridgeback

- Schnauzer

- Shar-Pei

- Staffordshire Terrier

- Weimaraner

- before surgery to shrink a tumour down

- after surgery if the tumour appears more aggressive on analysis of a biopsy

- as palliative treatment if a tumour cannot be removed, has already spread or if an owner does not want to pursue surgical intervention.

Some breeds tend to get MCTs more commonly in certain locations, but more importantly MCTs sometimes behave in a certain way in certain breeds. For example, Pugs are renowned for getting large numbers of low-grade (less aggressive) tumours, and Golden Retrievers commonly get multiple tumours. Boxers with MCTs are generally younger than other breeds, and more commonly have lower-grade MCTs with a more favourable prognosis. In contrast, Shar-Pei’s usually get aggressive high-grade and metastatic (spread to other sites) tumours, often at quite a young age. MCTs in Labrador Retrievers are also frequently more aggressive than in other breeds.

Age

The average age of dogs at presentation is between 7.5 and 9 years, although MCTs can occur at any age.

Paraneoplastic syndromes and complications of granule release

Cancerous mast cells contain 25 to 50 times more histamine than normal mast cells. Histamine is a very inflammatory chemical, and therefore explains why some MCTs wax and wane or suddenly increase in size due to inflammation – especially after they have undergone biopsy/needle aspiration (see diagnosis). Histamine also causes the stomach lining to produce more acid – this can result in stomach ulcers, causing signs such as vomiting or black, tarry stools (this appearance is due to the presence of digested blood coming from the ulcer).

The outlook (prognosis) –

Can we predict whether a dog will do well or not do well due to their MCT? No single factor accurately predicts the biological behaviour or response to treatment in dogs affected by MCTs. Various clinical factors can influence the outcome, such as whether it has spread, potentially the breed and also the tumour location. Tumours in the nail bed, inside the mouth, on the muzzle, in the groin area and in those sites where the skin meets mucus membranes (mucocutaneous junctions), are often correlated with a worse prognosis than those in other parts of the body, although this is not always the case.The single most valuable factor in predicting the outcome for most patients is the grade of the tumour when assessed under a microscope (the histological grade).

How is MCT diagnosed?

Cytology – This means looking at the cells under a microscope, and the sample for this is usually obtained by ‘fine-needle aspirate’. Fine-needle aspirates of MCTs involve taking a small sample of the tumour with a thin needle. This is generally a straightforward procedure which can be done conscious and without sedation in most patients. It should be performed prior to any surgery, because a pre-operative diagnosis of MCT influences the type and extent of surgical intervention required.

Biopsy - This involves taking a larger piece of tumour tissue and sending it away to a pathologist for analysis. This can be performed to help decide on the best treatment, or it can be performed when the tumour has been removed to find out the grade of the tumour.The pathologist looks at the sample of the tumour under the microscope and performs grading to indicate how aggressive the tumour is.

MCT grade and outlook (prognosis)

Low grade (grade 1) tumours and around 75% of intermediate (grade 2) tumours are cured with complete surgical excision. Unfortunately, most high grade (grade 3) tumours and around 25% of intermediate grade tumours have already spread by the time they are diagnosed (even if this spread cannot be detected on scans at the time of diagnosis). These cases benefit from chemotherapy treatment. In some dogs, further analysis of the biopsy samples is useful in determining the best management options. The tumour grade is very important in determining the appropriate therapy for dogs with MCTs.

Further investigations – ‘staging’ of the MCT

As well as performing fine needle aspiration and biopsies of the MCT to determine its grade, additional tests may be required to determine the stage of the tumour i.e. whether or not it has already spread. These further tests can include sampling of nearby lymph nodes, chest X-rays and abdominal ultrasound scanning. Which tests are performed will depend on a number if factors, and these will be discussed with you by the specialist.

Treatment options

Surgery is the cornerstone of management of MCTs, and complete surgical removal is often curative in dogs with low or intermediate grade MCTs. However, to achieve a cure, in some circumstances a significant amount of tissue surrounding the tumour must be excised to ensure that all the tumour cells are removed. This can require a high level of surgical experience and expertise, in order to perform complex reconstructive surgical techniques and may require referral to a specialist.

If complete removal is not possible, or where the tumour appears to be more aggressive (e.g. high-grade) then radiation therapy and chemotherapy treatments become more useful. The optimum treatment depends on the tumour grade, stage and other factors unique to the individual dog.

Chemotherapy can be used:

Fortunately, the drugs used for chemotherapy in MCTs are extremely well tolerated and most owners are very happy with their dog’s quality of life on treatment. A new group of drugs called tyrosine kinase inhibitors is also available – these block proteins (called tyrosine kinases) which are found on the surface of cancerous mast cells. They can be used where tumours cannot be surgically removed or have recurred despite previous treatments. They can have some side effects, but most dogs tolerate these drugs well.

In some instances referral may be recommended to an RCVS Recognised Specialist in the fields of both medical and surgical oncology. The expertise provided by a combination of medical and surgical cancer specialists has particular advantages in MCT treatment.

Summary

Dogs have a unique risk to develop MCTs in the skin, and they can be frustrating to manage, even for specialist oncologists.

Knowing what the best treatment is for an individual dog depends on knowing the grade of the MCT and whether or not it has already spread.

It is important to recognise that most dogs can survive for a long time with mast cell cancer and can be cured. However, some dogs have a more aggressive type of MCT and treatment in these cases is of a more palliative nature, trying to improve patient comfort and life expectancy, but without being able to achieve a cure.

If you have any queries or concerns, please do not hesitate to contact us.

Special Offer – October – 10% Off Anxiety Relieving Products

by admin on October 3rd, 2017

Category: Special Offers, Tags:

Pet of the month – October – Sophie

by admin on October 3rd, 2017

Category: Pet of the Month, Tags:

Sophie is recovering extremely well following the removal of a stick from her stomach using our new fibreoptic endoscope.

An endoscope is a long, thin, flexible tube that has a light source and camera at one end. Images of the inside of your body are relayed to a television screen.

Endoscopes can be inserted into the body through a natural opening, such as the mouth and down the throat, or through the bottom. An endoscope can also be inserted through a small cut (incision) made in the skin when keyhole surgery is being carried out.

Our three endoscopes range from one that is small enough to examine the nasal cavity to larger diameter ones for exploring the airways and gastrointestinal tract. It is amazing to be able to explore deep within the body yet with minimal trauma to the patient, and in this instance without the need for a surgical laparotomy to remove the stick. For Sophie this meant instant resolution.

Pet of the Month – September 2017 – Lola

by admin on September 2nd, 2017

Category: Pet of the Month, Tags:

We are delighted to report that Border Terrier Lola is recovering well from a procedure called gastrotomy in which an incision is made into the stomach under general anaesthesia.

Lola became unwell recently, quite out of the blue, and was in obvious abdominal pain. Medication was of little assistance so further investigation was undertaken. When a round opaque object was seen on radiographs of her abdomen an exploratory laparotomy was performed. A stone was located in and removed from her stomach.

Lola was a pleasure to look after and is now back to her former self as you can see in this picture.

Special Offer – September – Dental Offer

by admin on August 31st, 2017

Category: Special Offers, Tags:

Glaucoma

by admin on August 31st, 2017

Category: News, Tags:

What is glaucoma?

Glaucoma is an increased pressure inside the eye, caused by an obstruction to the drainage of the fluid from within the eye. In order to keep the eye inflated, fluid is normally produced and cleared away from the eye all the time. The fluid inside the eye is not related to the tear fluid (which is on the surface of the eye).

The blockage of fluid drainage within the eye can be due to an inborn defect (primary glaucoma) or due to another eye disease that interferes with drainage of the fluid inside the eye (secondary glaucoma). Common causes of secondary glaucoma are inflammation inside the eye or a shift of the position of the lens within the eye.

Is my dog at risk?

Many cases of primary glaucoma are inherited and due to an abnormally formed drainage passage within the eye. Affected breeds include the Basset Hound, Welsh Springer Spaniel, Cocker Spaniel, Siberian Husky, Great Dane, the Flat Coated Retriever and many others. Often one eye is affected initially but there is a high risk that the other eye will follow at some point in the future.

A test (gonioscopy) is available to determine the predisposition of your dog to develop glaucoma. In this test, a special contact lens is applied to the eye to allow assessment of the structure concerned with drainage of fluid from the inside of the eye.

What are the signs of glaucoma?

In most cases, the disease develops very rapidly. The patient is often depressed and reluctant to exercise. The eye becomes blind and appears red, painful and sore with a bluish tinge over the cornea. Less commonly, the pressure increase is slow and the clinical signs are not as pronounced. However, a gradual reduction in vision is often noticed.

How is glaucoma diagnosed?

A special instrument called a tonometer is used to measure the pressure inside the eye. Local anesthetic is applied to the eye for this test which is usually very well tolerated.

Is treatment possible?

The aim of treatment in glaucoma is to preserve vision and to relieve the pain caused by the pressure increase. In order to reduce the pressure within the eye, drugs are given to reduce fluid production within the eye and to improve removal of fluid from the eye. In some cases of secondary glaucoma (see previously mentioned), treatment of the underlying cause, such as anti-inflammatory medication or removal of a dislocated lens, can lead to the pressure decreasing.

Patients with primary glaucoma are more difficult to treat and it is important to realise that no cure for the disease exists. In some patients, pressure control can be achieved with medical treatment only. However, with time, most patients become less responsive to the treatment and surgical alternatives may have to be considered. These include laser therapy or the surgical placement of a drainage implant into the affected eye.

Regular check ups will also be necessary to re-assess the second eye and check its pressure.

Is preventative treatment available for the second eye?

No preventative treatment is available that can totally stop glaucoma developing in the second eye. However, there is evidence that with the help of medication, the onset of the condition in the second eye may be delayed.

What happens if the pressure cannot be controlled?

Eyes that have lost vision but continue to have an increased pressure are a cause of chronic pain for the patient. Removal of the eye must be considered in such cases to ensure the welfare and comfort of the patient. Occasionally, both eyes may, unfortunately, be lost. Should this be the case, most dogs will adapt very well to being blind and continue to lead a good quality life.

Syringomyelia

by admin on August 1st, 2017

Category: News, Tags:

Syringomyelia is a relatively common condition, especially in breeds like the Cavalier King Charles Spaniel and the Griffon Bruxellois, in which it is suspected to be an inherited disorder. Other names that have been used to describe this condition include syringohydromyelia, Arnold-Chiari or Chiari-like malformation, and caudal occipital malformation.

What is syringomyelia and what causes it?

Syringomyelia is a neurological condition where fluid filled cavities develop within the spinal cord (the bundle of nerves that run inside the spine). The most common reason for the fluid build-up is that there is an abnormality where the skull joins onto the vertebrae (the bones of the spine) in the neck, causing fluid in the brain (called cerebrospinal fluid or CSF) to be forced down the centre of the spinal cord, where it causes the tissues to become distended and cavities to form.

What are the most common signs of syringomyelia?

Clinical signs or symptoms can vary widely between dogs and there is no relation between the size of the syringomyelia (cavity in the spinal cord) and the severity of the signs – in other words a dog with severe fluid build-up can have relatively mild symptoms, and vice versa. The most common symptom that develops is intermittent neck pain, although back pain is also possible. Affected dogs may yelp and are often reluctant to jump and climb. They may feel sensations like ‘pins and needles’ (referred to as hyperaesthesia). Another common sign is scratching of the neck and shoulder region called ‘phantom scratching’, as there is generally no contact of the foot with the skin of the neck. Occasionally dogs become weak or wobbly if there is significant damage to nerves within the spinal cord. Cavalier King Charles Spaniels will typically show clinical signs between 6 months and 3 years of age. Not all dogs with syringomyelia will show signs of pain or other clinical symptoms, so the presence of syringomyelia can be an incidental finding on an MRI scan or specialised X-rays, when neurological investigations are being performed.

Other neurological conditions, such as slipped discs (cervical and thoracolumbar disc disease), can mimic the signs of syringomyelia and it is important for us to rule them out before concluding that your pet is suffering from syringomyelia.

How can syringomyelia be diagnosed?

The best method of diagnosing syringomyelia is an MRI scan of the brain and spine. It is necessary to perform this investigation under a general anaesthetic. The scan and anaesthetic are safe procedures. In the future it is possible there will be a genetic test to identify dogs with syringomyelia.

How can syringomyelia be treated?

Medical therapy is usually the treatment of choice in dogs suffering from syringomyelia. Several types of medication are used to manage episodes of pain, including a drug called gabapentin. This drug is safe, with few side effects apart from possible sleepiness. Other medications that may be used include anti-inflammatory drugs, corticosteroids and drugs that reduce the production of fluid in the brain and spinal cord.

Occasionally medical management is unsuccessful and surgery needs to be considered. The aim of surgery is to improve the shape of the back of the skull and reduce the flow of fluid down the centre of the spinal cord. Many dogs will improve following surgery, although some patients will have persistent signs despite surgery, whereas others may show improvement initially but then develop recurrence of their symptoms.

Pet of the Month – August 2017 – Harry

by admin on August 1st, 2017

Category: Pet of the Month, Tags:

Pet of the Month this August is Harry, a handsome 7 year old German Shepherd Dog. We are delighted to report that he has recovered extremely well following recent surgery for Gastric Dilatation.

What is gastric-dilatation and volvulus (GDV)? Is my dog at risk?

Gastric dilatation and volvulus, or GDV as it is commonly abbreviated, is a relatively common clinical syndrome seen in large / giant breeds of dog. Dilatation refers to bloating of the stomach with gas, and volvulus refers to twisting of the stomach about its axis. The cause of this syndrome is not completely understood. In fact it is quite controversial which occurs first; the bloat or the volvulus (twisting). Indeed both components do not have to occur together and some patients will develop relatively simple bloat alone. GDV is a potentially life threatening condition and emergency veterinary attention should be sought immediately if it is suspected.

Why is GDV potentially life-threatening to dogs?

There are a number of serious and potentially fatal consequences that occur as a result of GDV. Initially the severe distension of the stomach stretches the blood vessels over its surface reducing the blood supply to the stomach walls. This is made worse by the twisting of the stomach which also twists the blood vessels, effectively shutting off blood supply to the stomach. A lack of blood flow means there is a lack of oxygen and nutrients delivered to the stomach and waste products are not removed. As with any organ this will result in parts of it dying. This process happens very quickly and in severe cases could result in part of the stomach wall rupturing and releasing its contents into the abdomen.

The large distended stomach occupies much more space inside the abdominal cavity and compresses surrounding structures. Severe distension puts pressure on the diaphragm and interferes with the patient’s ability to breath. It also applies pressure to a large blood vessel in the abdomen (the vena cava) that normally returns blood from the back half of the body to the heart. Pressure on this vessel obstructs flow therefore reducing the amount of blood returned. If blood can’t be returned to the heart, then it in turn can’t pump it out to the rest of the body. If there is insufficient blood being pumped, the blood pressure falls dramatically making the patient weak and potentially leading to collapse.

To add insult to injury, other organs in the body such as the lungs, kidneys, liver and intestines do not receive a blood supply and begin to fail. The lack of a functional circulation also means that toxic products build up in these organs that further compromise the patient. These changes can happen in a matter of hours, emphasizing the importance of early veterinary attention.

What are the symptoms of GDV in dogs?

The symptoms generally include obvious distension or enlargement of the abdomen with unproductive vomiting or retching. The patient may drool excessively and appear restless or agitated. As the condition progresses the patient may become increasingly weak or even develop shock and collapse.

What is the treatment for GDV?

The age and breed of the patient coupled with the clinical signs of a severely bloated abdomen will make your vet highly suspicious of this condition. They will immediately place one or more an intra-venous catheters to allow administration of fluids to support the circulation and dilute toxins in the blood. They may also analyse the patient’s blood to assess the severity of organ damage.

The next stage involves attempts to decompress the stomach. This is usually accomplished by passage of a specially designed tube through the mouth down into the stomach. There is a gag that can be used to assist in this process but many patients will require sedation or anaesthesia to complete the task. It can be very challenging or sometimes impossible to perform stomach tubing. This is particularly the case when the stomach is twisted 360 degrees or more. In this instance a cannula (tube) may have to be inserted through the body wall and into the stomach to allow deflation. Deflation is clearly an imperative step because it will relieve pressure on the diaphragm and help restore blood flow back to the heart through the vena cava.

Radiographs of the abdomen are often required to help distinguish between simple dilatation and dilatation with volvulus. In the latter case surgery will be required as soon as the patient is stabilised. The aim of the surgery is to de-rotate the stomach and assess it for areas of devitalisation. If there are areas of the stomach that have undergone necrosis (died), these need to be removed surgically.

It is vital that the stomach is attached to the inside of the body wall. This is called a gastropexy and it will prevent volvulus in the future. This is essential as up to three quarters of the patients that do not have this performed will have another episode in the future. This also applies to those patients suffering with bloat alone as they have the same risk.

What are the risk factors for GDV in dogs?

There are several factors that have been clearly demonstrated to increase an individual’s risk of developing this condition. These include:

- Being a purebred large / giant breed

- Having a deep and narrow chest conformation

- Having a history of previous bloat

- Having a history of bloat or GDV in a first degree relative (parent or sibling)

- Increasing age

- Having an aggressive or fearful temperament

- Eating fewer meals per day

- Eating rapidly

- Being fed a food with small particle size

- Exercising or stress after a meal

What breeds are predisposed to this condition?

The breeds most commonly affected are large purebred dogs that have a narrow deep chest confirmation. Those at most risk include:

- Great Danes

- Gordon setters

- Irish setters

- Weimaraners

- St. Bernard’s

- Standard poodles

- Bassett hounds

Although these are the breeds we typically see GDV in, it is worthy to remember that it can happen in any patient.

What is the prognosis?

With improved understanding of the secondary consequences of GDV and excellent anaesthesia, surgical and post-operative care now available for veterinary patients a good prognosis can be achieved for this condition. Survival rates of 73-90% would be typical. There will always be a range quoted for survival because individual patient’s circumstances in terms of severity, age, general health and treatment received will have an impact on the outcome. One important factor that has been shown to decrease the survival is the presence of clinical signs for greater than six hours. This emphasizes the importance of prompt veterinary attention in all cases.

If you are in any doubt that your dog is suffering from bloat or GDV, please call your vet immediately.

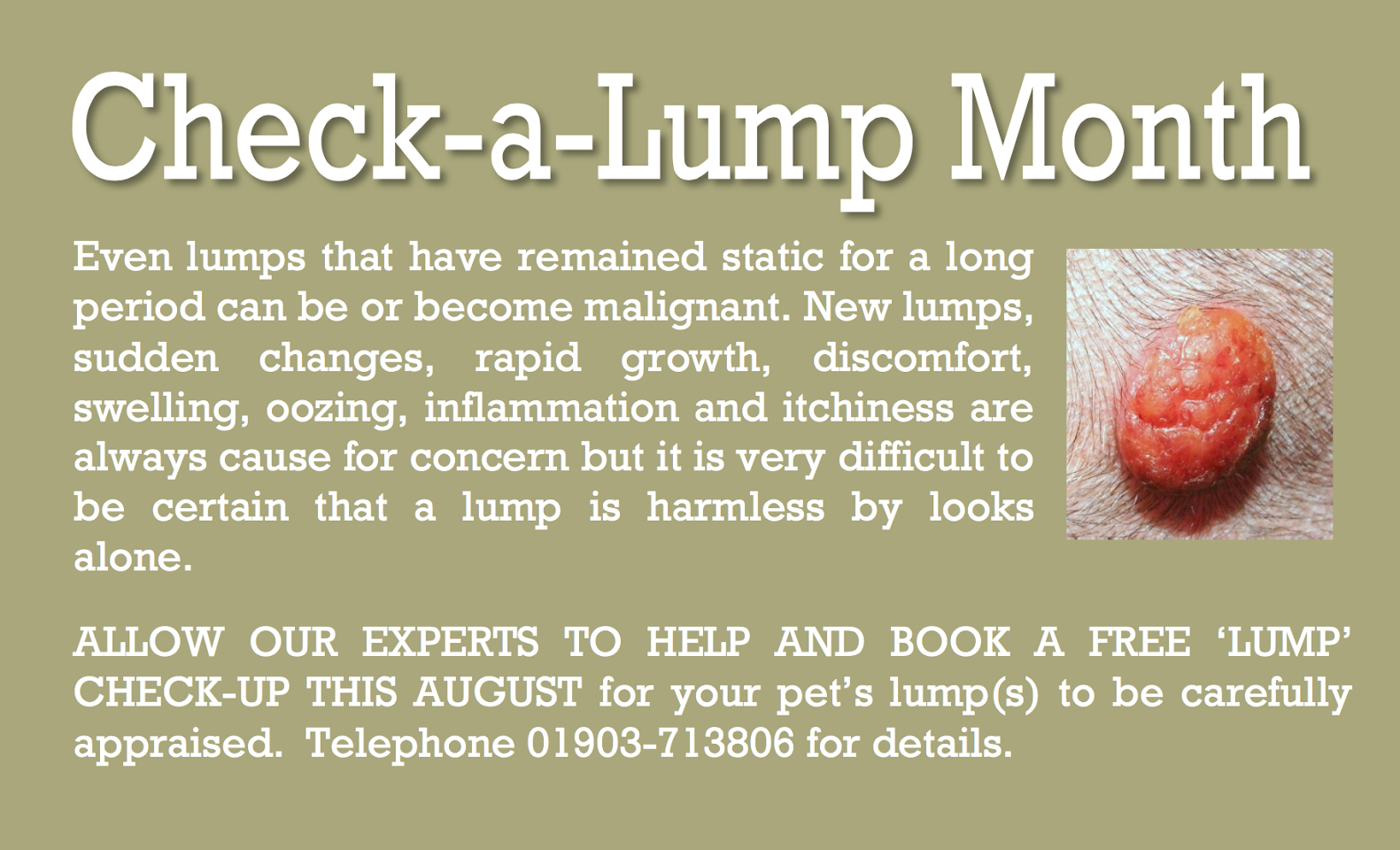

Special Offer – August – Check a lump month

by admin on August 1st, 2017

Category: Special Offers, Tags: